Participation/Resources/2014 Community Survey

2015 Mozilla Contributors Study

David Eaves Peter Loewen

February 9, 2015

Introduction

The continued production and widespread adoption of freely available software relies not only on an excellent product, but as importantly on the thousands of volunteers who devote their time, energy, and expertise to Mozilla. As such, Mozilla stands apart from other technology companies.

Why do such individuals contribute? What drives their desire to contribute more in the future? And what barriers stand in the way of their contributing?

In this report, we use both self-reported information from Mozillians as well as actual data on their contributions to learn more about several dimensions of contribution. In Section 1, we consider how Mozillians’ contribution experiences and their knowledge about Mozilla matter for their contributing going forward. We identify several important drivers. In Section 2, we consider how these factors vary both by functional group and by country. In Section 3, we identify different work patterns among Mozilla contributors, taking particular note of the differences between the most effective and long-standing contributors and others. In Section 4, we present important data on both barriers to contributing and rewards for contributing. We conclude with a summary of key findings and six recommendations.

Section 1: The Drivers of Contributions

Why do some individuals contribute to Mozilla more than others? And why do some foresee greater contributions in the future than others?

We are interested in three measures of contribution. First, the anticipated rate of contributor “on-ramping” – the likelihood that they would help bring additional contributors to the community - in the future. As a means of growing the Mozilla community, on-ramping is a central activity. Because the baseline rate of on-ramping can vary across functional groups, we ask respondents whether they anticipate doing more, less, or the same amount of on-ramping in the future. Our second measure of contribution is an indicator of whether community members are making active contributions, as captured by the Mozillian Community project (see our Methodology section for more details). Third, we measure the rate at which individuals are contributing to the community in the form of contributions per day.

For each of these outcomes, we consider three possible drivers:

- Contributors’ knowledge of Mozilla’s overall goals;

- Contributors’ perceptions of their past and future impacts on Mozilla; and,

- The quality of contributors’ recent experiences in working with Mozilla (we discuss this measure in more detail in Section 2).

Our first driver - contributor knowledge of top-level goals - is simply a self-report on whether a contributor claims to be familiar with Mozilla’s goals. Our second driver is captured in responses to the questions “Thinking back to one year ago, how much impact do you think your work has had on Mozilla?”, and, “Thinking ahead one year, how much impact do you think your current work will have at Mozilla?” Our final driver is captured in a predicted score from a factor analysis of eight items related to recent contributor experiences. Those with a higher score indicate more positive recent experiences (note: All of these variables are rescaled from 0-1, from their minimum to the maximum values).

For each of our outcomes – on-ramping, contributor status, and contribution rate – we estimate a functionally-appropriate regression. This allows us to estimate the impact of several drivers simultaneously, while netting out any effects due to function group of country. Our full regression results are available in Tables 1-3 at the end of this report.

Results

Future On-Ramping

We begin by analyzing the predictors of expected future on-ramping activity. We again underline that this is capturing a perception of how much individuals believe they will try to on ramp other contributors in the future, compared to how much they are on-ramping at present.

Four results are most notable. First, knowledge of Mozilla’s top-level goals does not have a reliably estimable effect on the likelihood of future on-ramping. However, knowledge of these goals is important for other outcomes, as we will show.

Second, recent experiences are predictive of future engagement with Mozilla. The more positive a contirbutor’s self-assessment of recent experiences, the more likely they are to expect to increase their future relative on-ramping. The substantive effect of this is very impressive. Those with the worst recent experiences have a likelihood of increasing their on-ramp rate of just 19%. This grows to 66% among those with the most positive recent experiences, net all other factors.

Third, the role of future and past impacts is contradictory (and perhaps counterintuitive). Our results suggest that those who anticipate a positive future impact are more likely to increase their on-ramping rate. The substantive effect is impressive, ranging from a 25% likelihood of increasing on-ramping among those with the lowest estimates of future impact to 54% among those with the highest impact. This effect is obviously not as impressive as that generated by recent experiences. However, while perceived future impact matters positively, perceived past impact matters negatively. Those with the most positive past impact are 13 points less likely to increase future on-ramping as those with the least positive past impact (43% versus 56%). Further analysis explains this result. When our model is estimated without future impact, past impact has no appreciable effect whatsoever. Moreover, past impact is positively correlated with future impact, confirming the reasonable inference that individuals’ past experiences colour how they view the future. Taken together, there is an important substantive point in these findings. Namely, individuals who have had positive past impacts but do not think they will have a positive future impact are less likely to increase their engagement than those who have has a negative past impact. More colloquially, if a contributor thinks the future is bleak, those who have made their mark will be less likely to contribute than those who are yet to have a positive impact.

Finally, we note that no measurable differences in anticipated future on-ramping by functional groupings. We examine other differences by both functional group and contributor country in the next section.

Being a contributor

In addition to anticipated future on-ramping, we also consider actual rates of contribution. We divide contributors into two groups, according to whether they are above or below the median of total recorded contributions (note: The results presented here do not differ materially if we measure the total number of contributions).

Three results of note emerge:

- First, those who have had a greater perceived impact in the past are more likely to be among the upper half of contributors.

- Second, those who are familiar with Mozilla’s top line goals are more likely to have made more contributions. The effect is impressive. Among those who are not familiar with Mozilla’s topline goals, the likelihood of being among the frequent contributors is 24%. This climbs to 39% among those who are familiar with topline goals.

- Third, we find that more positive recent volunteer experiences are correlated with a greater likelihood of being within the top half of contributors. Among contributors with the most negative recent experiences, 12% are in the top half of contributors. For those with the most positive experiences, 47% are among the top contributors.

Rates of Contribution

Our final metric concerns the contribution rate of Mozillians. Whereas the previous measure captured whether a contributor was in the top or bottom half of all contributors, our rate measure captures how many contributions they make per day, on average. This has the effect of rendering equal, for example, a one-year and a five-year contributor, provided they are both contributing the same amount per day, on average.

On this metric, only two factors are particularly notable. First, past impact is correlated with the current rate of contributing. This suggests that the rate of contributory behaviour (as opposed to anticipated future contributions), is shifted upwards among those with more positive past experiences. Second, we again find that more knowledge of Mozilla’s top-level goals is associated with a greater rate of contribution. It is important to note that we find no relationships between the rate of contributions and contributors’ assessments of their recent experiences. We likewise find no relationship between rates of contribution and anticipated future impacts.

We derive several recommendations from these findings. These can be found in Section 5.

Section 2: Sources of impact evaluations and recent experiences

In Section 1, we demonstrated that three classes of factors matter for contributing to Mozilla, namely knowledge of Mozilla’s top-level goals, perceptions of past and future impact, and their recent experiences with Mozilla.

In this section, we examine the correlates of these factors. First, we examine how these factors vary, both by country and by functional group. Second, we then unpack further which things contribute to more positive recent experiences.

The Mozilla contributors community works across several different functional groups. We group individuals into six different groups (with percentages in parentheses indicating how many individuals in our sample are in the respective grouping):

- Add On (3%)

- Branding (21%)

- Coding (24%)

- Localization (27%)

- Support (6%)

- Other (19%)

Evaluations of Impact

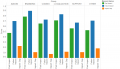

We find some notable differences between these groups in terms of their evaluations of the contributor experience. Figure 1 demonstrates the mean evaluations of past and future impact by grouping. It also presents a measure of the “impact gap” between perceived future and past impacts.

Beginning with evaluations of past impact, we note substantial variation, from a low of approximately 0.48 among those in Add On and 0.53 among those in Other, to 0.89 among those in Branding. To quantify this difference further, we can translate these differences in evaluations into differences in behaviour according to the models in Section 1. For example, the model of rates of contributions suggest that those with an evaluation of past impact of 0.48 would make, on average, 0.60 contributions per day. Among those with an evaluation as high as those in Branding, the average contributions per day would be 0.72, net all other factors. This is a difference of 20%, or 3.6 contributions in the average month.

Similar variation exists among evaluations of future impact. The highest scores are registered once again among those in Branding. Those in Localization, Coding, and Add On also exhibit impressively high perceptions of future impact. The lowest perceptions are among those in Support and those in the Other category. We do note, however, that the magnitude of the effect of perceptions of future impact in the models in Section 1 is generally lower. Accordingly, these differences across groups in future impact likely have less bearing than those in past impact.

Finally, we can consider the “impact gap” within groups, namely by comparing the difference between future and past impact. We note that every group, on average, is more optimistic in evaluations about the future than they are in their retrospections. Accordingly, gaps are not on their own causes for any concern. Rather, they suggest a general positivity about the potential for the future. The biggest gaps exist among those in Add On and Other. For all other categories, there is greater alignment of their impact in the past and future.

Starker differences emerge in perceptions of past and future impact emerge if we consider differences between countries. While this study relies on responses from more than 40 countries, we limit our comparisons to 9 countries. This is largely due to a need for a minimum number of observations, which we set at 29 (the number in the United Kingdom). Our results are presented in Figure 2.

Beginning with evaluations of past impact, we see that these are lowest in France and Brazil. Evaluations are noticeably highest in India, Indonesia, and Canada. Similar patterns obtain in evaluations of future impact, with France once again registering the lowest score, followed by Germany. Evaluations are comparatively bullish in India, Bangladesh, and Indonesia.

Finally, the greatest gaps are witnessed in Brazil, Bangledesh, and India. Other countries appear more aligned in their evaluations of past and future impact.

Knowledge of Top Level Goals

As Section 1 demonstrates, knowledge of Mozilla’s top-level goals is associated with greater likelihood of being a contributor and with a greater rate of contribution. Accordingly, it is important to understand how knowledge of Mozilla’s top-level goals varies by functional group and by country.

Figure 3 shows results by functional group. Knowledge of top-level goals is lowest among those in the catchall Other category (32%) and in the Support category (34%). It rises as high 62% among those in Branding. In only two other categories (Add On and Coding) are the majority of individuals aware of Mozilla’s top-level goals. These differences are not inconsequential. According to our estimates in the Section 1 models, a 28 percentage point difference in knowledge of top-level goals is associated with an increase from 0.31 to 0.65 contributions per day; and with an increase in the likelihood of being a contributor for 24% to 39%.

Knowledge of top-level goals also varies appreciably by country. In only three countries -- France, Canada, and India -- do the majority of respondents indicate that they are familiar with the top-level goals. However, in most other countries the rate of familiarity falls between forty and fifty percent. In only Brazil is the rate below that, where it registers at a just 26%.

The importance of recent experiences

Finally, we consider the recent experiences of contributors. Recall that our measure of recent experiences is a “factor” score, ranging from 0 for those with the most negative recent experiences to 1 for those with most positive recent experiences. We find few important differences across either functional grouping (Figure 5) or country (Figure 6). Among functional grouping, the range of average recent experiences ranges from 0.58 (Other grouping) to 0.66 (Localization). Among our country groups, the most negative recent experiences are among those in the United States (0.57). The most positive present among those in Bangladesh (0.70).

If average recent experiences do not vary much by country or grouping, this does not mean that they are unimportant for our contribution outcomes. To the contrary, recent experiences matter both for being a contributor today and anticipating increased contributions in the future. Accordingly, we think it is important to understand what underlies positive recent experiences. As indicated in Section 1, our measure of the quality of recent contributor experiences is captured in a factor analysis score. This score considers respondents’ levels of agreement with seven different statements about their most recent contribution:

- My most recent contribution was a positive experience;

- My most recent contribution was an effective use of my time;

- I think my most recent contribution made a real difference for Mozilla;

- I found my most recent contribution frustrating and unproductive;

- My recent contribution did not have as much impact as I had hoped;

- I find it hard to coordinate with other volunteers;

- It was always clear to me how I could contribute; and,

- I felt like my contribution was no appreciated by Mozilla staff.

These measures all load onto a single dimension, suggesting that each element reflects a common experience. Some elements, however, matter more than others.

Our data analysis suggests that the four most important contributors to a positive recent experience are:

- not agreeing that a contribution was frustrating and unproductive,

- agreeing that the experience was positive,

- disagreeing that the experience did not have as much impact as hoped, and

- agreeing that contribution was an effective use of the contributor’s time.

Taken together, these results suggest that evaluations of experience can be understood as a global reading of an individual’s interactions with Mozilla, rather than reflecting one particular part of the contribution experience.

Section 3: Work Patterns

As a part of our study, we asked respondents several questions regarding their work habits with Mozilla, namely how they set aside time to work on Mozilla projects, whether their work for Mozilla resembled their other work, and how much they interacted with other Mozillians. By examining how different work patterns correlate with different levels of contribution, we can reveal important differences between established and new contributors, and better map out a path to sustained engagement.

Our approach to identifying the work habits of those who are the greatest contributors is two fold. First, we identify those in the top quartile of contributions per day. This captures the rate at which individuals are contributing, and effectively weights evenly those who are recent contributors and those who are longstanding contributors. However, we also want to capture the tenure of contributions. Accordingly, we divide contributors once more according to whether their tenure as a contributor is more or less than one year. This produces four types of contributors:

- New-High contributors

- New-Low contributors

- Established-High contributors

- Established-Low contributors

These types of contributors vary in how they organize their contributions to Mozilla in important ways. First, we asked respondents about their general approach to planning their contributions to Mozilla. Three answers were available:

- I set aside a certain amount of time for Mozilla work each week;

- I set aside as much time as a Mozilla project requires; and,

- I work on Mozilla projects only when I feel I have the time.

Established-High contributors are the most likely (68%) to indicate that they set aside a certain amount of time or as much as is required. By contrast, Established-Low and New-High contributors only agree with those two statements 49% of the time. New-Low contributors agree with those statements 57% of the time. The key takeaway, in this instance, is that New contributors who are making an impact most resemble Established contributors who are making less of an impact. The important shift, then, is towards one in which time is prioritized and set aside for Mozilla projects.

Our second potential difference in work style is in the specialization of work, namely whether Mozilla contributors were engaging in work similar to what they do on projects outside of Mozilla, or if their work from Mozilla differed. The most notable difference here is not between established and new contributors, but high and low rate contributors. High contributors are more likely than low contributors to report that their work at Mozilla differs from what they do in other paid and volunteer engagements (71% versus 66%). These High contributors can bring diverse skills to their projects and work outside of regular areas of expertise or comfort.

Our third difference is how many times in an average week a respondent interacts with other Mozillians when working on a project, whether rarely, once or twice, at least once a day, or several times a day. Rates of interaction differ only for one group, namely Established-High contributors. These individuals are, on average, one category of interaction higher than all others.

Taken together, a picture emerges of what sets apart established and high contributors. They bring to bear diverse skills, they regularly interact with other Mozillians, and they do so within the context of time dedicated to Mozilla’s projects.

Section 4: Barriers and Rewards

The first sections of our report considered the factors that explain contributions to Mozilla. The preceding section considered the differing work patterns of contributors. We now consider the barriers to contributing which Mozillians identify; and the value they place on various rewards for contribution. Before presenting these, we wish to note that these factors rarely exercise any independent effect on whether Mozillians contribute. In other words, when we control for a respondent’s evaluations of their past impact and perceived future impact, for their knowledge of top-level goals, and for their recent volunteer experiences, there is no remaining effect either for rewards or barriers. Nonetheless, it can be useful to consider the views of Mozillians on these issues.

Barriers

We presented respondents with seven potential barriers to contribution. These barriers are as follows, with the percentage of respondents who agreed in parentheses.

- not enough time (59%);

- communications on processes are unclear and the respondent does not know where to find information (24%);

- Respondent feels overwhelmed by the number of things to do (20%);

- not enough tools or infrastructure (18%);

- Respondent does not have the skills to participate (13%);

- no one asks for help (11%);

- Community is unfriendly (7%).

There is one clear barrier to participation: insufficient time. The next two most important factors apply to just one-in-four contributors at most, and one of these -- feeling overwhelmed -- is closely related to a shortage of time. The upshot, then, is that the biggest factors limiting contributions do not have to do with either Mozilla’s processes or its culture, but with time simple allocation.

These self-reported barriers to contributing are particularly important in light of the findings in the previous section. The most relevant differences between Established High contributors and all other contributors is that they set aside time for Mozilla work, and they regularly interact with other Mozillians. Such individuals are less likely to feel overwhelmed, and are more likely to know where to mind information to answer their questions.

Rewards

Finally, we consider the potential benefits that individuals accrue from contributing to Mozilla. Our survey asked respondents what they find most useful about contributing to Mozilla. Figure 7 presents our results, broken up by low and high contributors. The results are telling. First, the opportunity to travel to meet ups and related events is the least important benefit that contributors receive. Lest this be mistaken for misanthropy, the most important benefit is “meeting other people.” Second, being recognized for their contributions is the second least important. Third, the most important differences between low and high contributors are meeting others (with high contributors prizing this more), understanding goals (with this being less important to high contributors), and learning new skills (with this being less important to high contributors). These results underline two important points. First, for the high contributors, the most important rewards are truly social rather than symbolic or material. For low contributors, socialization into Mozilla -- in this case learning skills and Mozilla’s goals -- are the most prized activities.

Section 5: Key Findings and Recommendations

Key Findings

- Recent experiences matter for on-ramping. Those with the worst recent experiences have a likelihood of increasing their on-ramp rate of just 19%. This grows to 66% among those with the most positive recent experiences, net all other factors.

- Having an impact in the past is not enough for future on-ramping. Those who have had positive past impacts are less likely to increase on-ramping in the future. This can be overcome by estimating a positive future impact.

- Contributors recognize their impact. High contributors are more likely to feel they’ve had an impact in the past than low contributors. Recognition is important.

- Contributors know Mozilla’s goals. Those who are knowledgeable about Mozilla’s top level goals are more likely to be contributors. They also make more contributions – on average 10 more contributions a month.

- Contributors have positive volunteer experiences. Those who have had positive recent experiences are more likely to be contributors.

- Setting aside time for Mozilla work is the key to successful contributions. The biggest barrier to contributing is time to complete projects and learn new skills. Mozillians who set aside time for Mozilla work are more likely to contribute and contribute for longer periods of time; they are more likely to work on diverse tasks; and they are more likely to interact with other Mozillians.

Recommendations

Based on this report, we forward 6 different recommendations in 3 different domains.

Engagement

- Among the greatest barriers to participation are time and a lack of skills for a particular project. Monitoring stalled contributions and reaching out to contributors can prevent drop-out and move contributors from New to Established.

- New contributors should be engaged and embraced by the community as soon as possible. They should be made aware of the nature of their impact, not just recognized for making a contribution. They should be introduced to other Mozillians, especially those who are Established-High contributors. They should be made aware of Mozilla’s top level goals.

Impact

- The impact of past contributions should be easily understood. The potential impact of new contributions should be equally expressed.

- Social rewards are more important than formal recognition. Processes and tools that bring Mozllians together (if only virtually) are more important for positive experiences than formal recognitions. Accordingly, we should focus on making connections between contributors.

Data

- Teams and functional groups should continually collect data, not only on contribution rates and types, but also on contributor experience and impact.

- Data on impact and experiences should be regularly shared as means of monitoring sentiments, identifying successes, and paying attention to potential problems.

Methodology

Beginning on October 29, 2014, we administered an online survey to Mozilla contributors. The survey was open to any Mozillians, and was advertised across several platforms and lists. The survey registered 1162 completions. Eighty-five percent of respondents identified as male, 13% identified as female, and 2% identify as transgendered. The nine most frequent respondent countries were Bangladesh (3.5%), Brazil (3.0%), Canada (3.5%), France (4.7%), Germany (3.5%), India (14%), Indonesia (3.0%), the United Kingdom (2.5%) and the United States (16.3%). The remainder of respondents (45%) came from countries with less than 2.5% of respondents.

In addition to self-reported data, we merged real contribution data - including information on the total number of contributions and the date of initial contribution - from the Mozillian Community project. Such data were available for 779 respondents.

Our survey and data merges screened to ensure conformity with Mozilla’s Privacy Policy. All analysis was performed in STATA13.

Slides

The presentation's slides can be found here