IonMonkey/Overview: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

For example, consider an Ion-generated method having a 32-bit addition. If the addition operation overflows, or say it relies on an object access which happens to return a double, the compiled code is no longer valid. Guards check these assumptions, and when they fail, the method's execution resumes in the interpreter (and may later be recompiled). | For example, consider an Ion-generated method having a 32-bit addition. If the addition operation overflows, or say it relies on an object access which happens to return a double, the compiled code is no longer valid. Guards check these assumptions, and when they fail, the method's execution resumes in the interpreter (and may later be recompiled). | ||

When a guard fails, it is called a ''bailout'', which is explained later. | |||

=Pipeline= | =Pipeline= | ||

Revision as of 06:11, 15 August 2011

Modus Operandi

IonMonkey has two major goals:

- Have a well-engineered design that easily supports adding new optimizations.

- Allow for specialization needed to generate extremely fast code.

To support 1, IonMonkey has a somewhat highly abstracted codebase with many files. This document serves to help navigate them and the compiler framework.

To support 2, IonMonkey follows in the tracing JIT's stead. It supports optimistic assumptions about the effects and results of operations, and allows these assumptions to flow throughout the generated code. Like the tracer, this requires guards. Guards are strategically placed checks which will cause deoptimization if the check fails.

For example, consider an Ion-generated method having a 32-bit addition. If the addition operation overflows, or say it relies on an object access which happens to return a double, the compiled code is no longer valid. Guards check these assumptions, and when they fail, the method's execution resumes in the interpreter (and may later be recompiled).

When a guard fails, it is called a bailout, which is explained later.

Pipeline

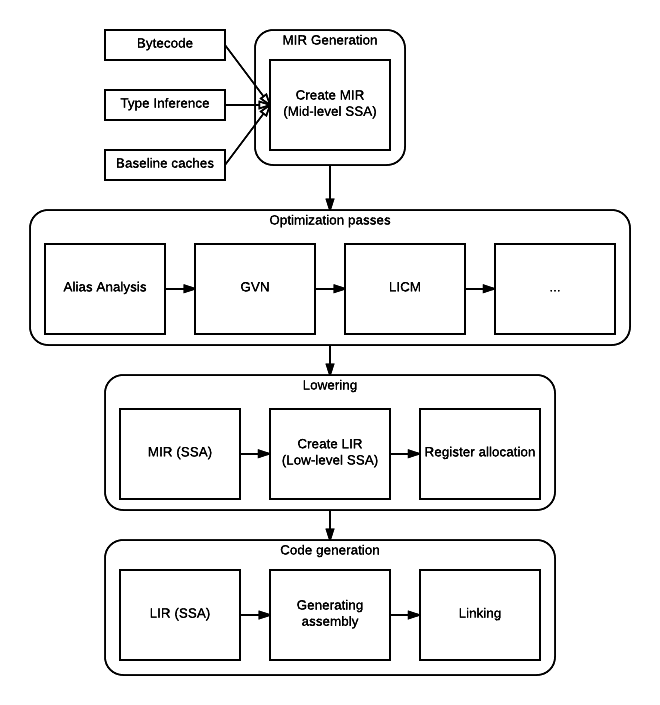

IonMonkey compilation occurs in four major overall phases:

- MIR Generation. This phase transforms SpiderMonkey's bytecode into a control-flow graph and an architecture-independent, SSA-form IR.

- Optimization. The MIR is analyzed and optimized. This is where global value numbering (GVN) and loop-invariant code motion (LICM) occur.

- Lowering. The MIR is transformed into an architecture-specific IR (still in SSA form) called LIR. Register allocation occurs on LIR.

- Code generation. The LIR is transformed into native assembly for x86, x64, or ARM (or what have you).

The full pipeline is roughly outlined with the following diagram:

Each major phase of the pipeline is separated into four articles:

Lastly, if you're interested in porting IonMonkey to a new CPU architecture, you might want to take a look at IonMonkey/Porting.

Runtime

IonMonkey does not interact with the VM in the same way as the interpreter. It does not build interpreter stack frames and does not maintain an interpreter-readable stack. However, IonMonkey does create its own stack frames, and may need to translate these frames back to interpreter frames (and vice-versa). These concepts are explored below.