Identity/AttachedServices/KeyServerProtocol

PiCL Key Server / IdP Protocol

NOTE: This specification is under active development (27-Jun-2013). Several pieces are not yet complete. If you write any code based on this design, keep a close eye on this page and/or contact me (warner) on the #picl IRC channel to learn about changes. Eventually this will be nailed down and should serve as a stable spec for the PICL keyserver/IdP protocol.

The test vectors included on this page were produced by the python code in https://github.com/warner/picl-spec-crypto . The diagrams may lag behind the latest version of that code.

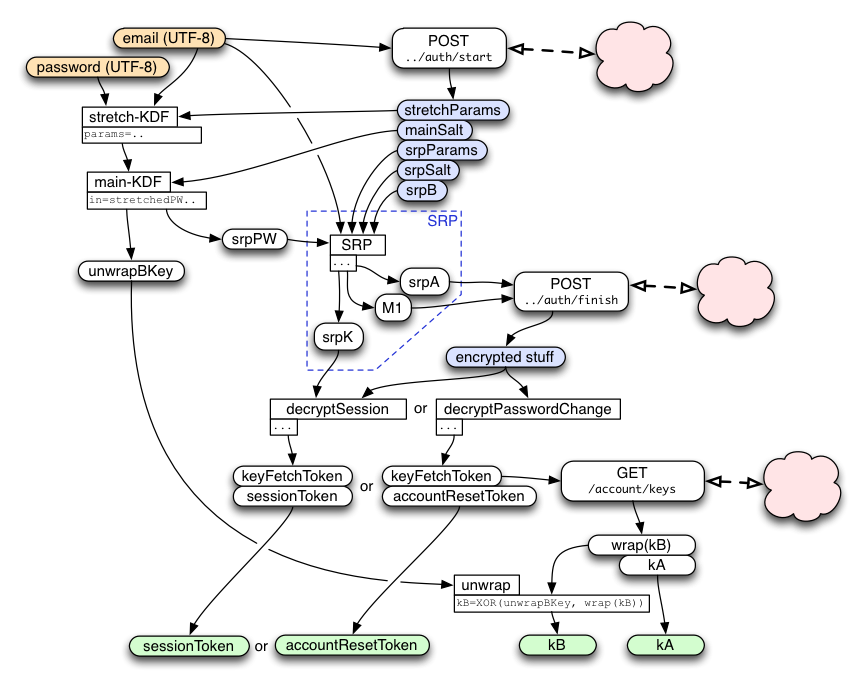

Email+Password -> SignToken/ResetToken

The first interaction with the keyserver takes an email+password pair and receives back (kA, wrap(kB), token). This starts by using key-stretching to transform the email+password into a "masterKey", then feeds this into an SRP protocol to get a session key. It uses this session key to decrypt a bundle of encrypted data from the keyserver, resulting in three values: kA, wrap(kB), and the signToken (or resetToken). The masterKey is also used to derive the key that will decrypt wrap(kB) into the actual kB value.

This same protocol is used, with slightly different methods and constants, to obtain the "resetToken".

The protocol is optimized to minimize round-trips and to enable parallelism. As a result, the two messages it sends (getToken1 and getToken2) each perform multiple jobs.

getToken1

As soon as the user finishes typing in the email address, the client should send it in the "getToken1" message to the keyserver. The response will include a set of parameters that are needed for key-stretching (described below), and the common parameters used by both sides of the SRP protocol to follow. These are simply looked up in a database entry for the client, along with an account-id. It must also include an allocated session-id that is used to associate this request with the subsequent getToken2 request. Finally, the response also includes the server's contribution to the SRP protocol ("srpB"), which is calculated on the server based upon a random value that it remembers in the session.

Proof-Of-Work

To protect the server's session table memory and CPU usage for the initial SRP calculation, the server might require clients to perform busy-work before calling getToken1(). The server can control how much work is required.

The getToken1() call looks for a "X-PiCL-PoW:" HTTP header. Most of the time, clients don't supply this header. But if the server responds to the getToken1() call with an error that indicates PoW is required, clients must create a valid PoW string and include it as the value of an "X-PiCL-PoW:" header in their next call to getToken1().

The server's error message includes two parameters. The first is a "prefix string": the client's PoW string is required to begin with this prefix. The second is a "threshold hash". SHA256(PoWString) is required to be lexicographically earlier than the thresholdHashString (i.e. the numerical value of its hash must be closer to zero than the threshold). The client is expected to concatenate the prefix with a counter, then repeatedly increment the counter and hash the result until they meet the threshold, then re-submit their getToken1() request with the combined prefix+counter string in the header. If the client has spent more than e.g. 10 seconds doing this, the client should probably help the user cancel the operation and try again.

When a server is under a DoS attack (either via some manual configuration tool or sensed automatically), it should start requiring valid unique X-PiCL-PoW headers. The server should initially require very little work, by using a threshold hash with just a few leading zero bits. If this is insufficient to reduce the attack volume, the threshold should be lowered, requiring even more work (from both the attacker and legitimate clients).

The server should create a prefix string that contains a parseable timestamp and a random nonce (e.g. "%d-%d-" % (int(time.time()), b32encode(os.urandom(8)))). The server should also decide on a cutoff time (perhaps ten minutes ago). Each server must then maintain a table of "old PoW strings" to prevent replay attacks (these do not need to be shared among all servers: an in-RAM cache is fine).

When the server receives a proposed PoW string, it first splits off the leading timestamp, and if the timestamp is older than the cutoff time, it rejects the string (either by dropping the connection, or returning a new "PoW required" error if it's feeling nice). Then it hashes the whole string and compares it against the threshold, rejecting those which fail to meet the threshold. Finally, for strings that pass the hash threshold, it checks the "old strings" table, and rejects any that appear on that list.

If the PoW string makes it past all these checks, the server should add the string to the "old strings" table, then accept the request (i.e. compute an srpB value and add a session-id table entry for the request).

The old-strings table check should be optimized to reject present strings quickly (i.e. if we are under attack, we should expect to see lots of duplicates of the same string, and must minimize the work we do when this occurs).

The server can remove values from the old-strings table that have timestamps older than the cutoff time. The server can also discard values at other times (to avoid consuming too much memory), without losing anything but protection against resource consumption.

Other notes:

The server-side code for this can be deferred until we care to have a response to a DoS attack. However the client-side code for this must be present from day one, otherwise we won't be able to turn on the defense later without fear of disabling legitimate old clients.

The server should perform as little work as possible before rejecting a token. Every extra CPU cycle it spends in this path is increasing the DoS attack amplification factor.

The nonce in the prefix string exists to make sure that two successive clients get different prefixes, and thus do not come up with the same counter value (and inadvertently create identical strings, looking like a replay attack). If this proved annoying or expensive, we could instead obligate clients to produce their own nonce.

TBD: Is this worth it? Should the PoW string go into an HTTP header? (I want it to be cheap to extract, and not clutter logs). Should the error response be a distinctive HTTP error code so our monitoring tools can easily count them? We can also use this feature to slow down online guessing attacks (i.e. trigger it either when getToken1 is called too much or when getToken2 produces too many errors). Since getToken1() includes an email address, we could also requires PoWs for some addresses (e.g. those we know to be under attack) but not others.

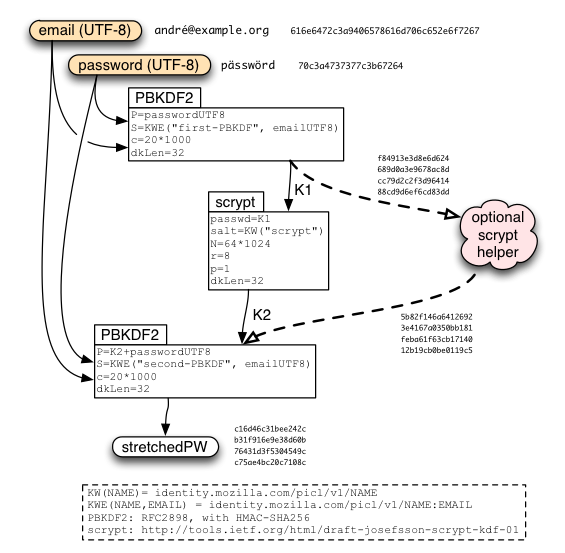

Client-Side Key Stretching

The current stub does no stretching. It just performs a single HKDF operation, combining the user's email address, their password, and a "stretchSalt" retrieved from the server's getToken1() response.

A later version of the protocol will replace this with the PBKDF2+scrypt+PBKDF2 protocol described in Identity/CryptoIdeas/01-PBKDF-scrypt. This stretching is expected to take a second or two. The client can optimistically start this process (using default parameters) before receiving the getToken1() response, and then check that it used the right parameters afterwards (repeating the operation if not). (We'll want to build the stretching function with periodic checkpoints so that we don't have to lose all progress if the parameters turn out to be wrong). The "stretchSalt" is added *after* the stretching, to enable this parallelism (at a tiny cost in security).

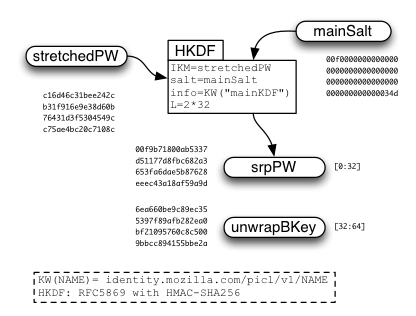

After "masterKey" is derived, a second HKDF call is used to derive "unwrapKey" and "srpPW" which will be used later.

SRP Protocol Details

The PiCL client uses the SRP protocol (http://srp.stanford.edu/) to prove that it knows the account password without revealing the actual password (or information enabling a brute-force attack) to the server or any eavesdroppers.

SRP is somewhat underspecified. We use SRP-6a, with SHA256 as the hash, and the 2048-bit modulus defined in RFC 5053 Appendix A. We consistently zero-pad all string values to 256 bytes (2048 bits), and use H(A+B+S) as the key-confirmation message "M1". These details, plus the SRP design papers and RFCs 2945 and 5054, should be enough to build a compatible implementation. The diagrams below are annotated with test vectors to verify compatibility.

The server should use Jed's SRP module from https://github.com/jedp/node-srp . The client might use SJCL (http://crypto.stanford.edu/sjcl/) or native code (NSS).

The basic idea is that we're using the main-KDF output "srpPW" as a password for the SRP calculation. We use the email address for "identity", and a server-provided string for "salt". (We could safely leave them blank, since equivalent values are already folded into the password-stretching process, but it's less confusing to follow the SRP spec and fill them in with something sensible).

Note that SRP-6a uses a "k" value which basically encodes the group being used ("N" and "g"). Since all PICL accounts use the same 2048-bit group, they will all use the same "k" value (not to be confused with the per-session shared-secret "K" key that emerges from the protocol). This group's "k" integer is (as a base-10 number): 259003859907 09503006915442163037721228467470 35652616593381637186118123578112

The following examples use a non-ASCII email address of "andré@example.org" (with an accented "e", UTF8 encoding is 616e6472c3a9406578616d706c652e6f7267) and a non-ascii password of "pässwörd" (with accents on "a" and "o", UTF8 encoding is 70c3a4737377c3b67264). Given the password-stretching described earlier, this results in an srpPW of: 5b597db713ef1c05 67f8d053e9dde294 f917a0a838ddb661 a98a67a188bdf491

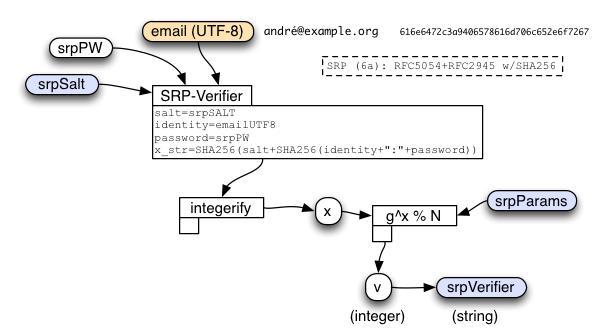

SRP Verifier Calculation

When the client first creates the account, it must combine the account email address, the stretched password (srpPW), and a randomly-generated srpSalt, to compute the srpVerifier. The server will use this verifier later, to check whether or not the client really knows the password.

If the server is compromised and an attacker learns the srpVerifier for a given account, they cannot use this to directly log in (the verifier is not "password-equivalent"), but it does allow them to perform an offline brute-force attack against the user's password. In this respect, it is similar to a traditional hashed password. We make these attacks somewhat more expensive by performing the client-side stretching described above, instead of using the raw user password in the SRP calculation.

Given the sample email and password above, the SRP Verifier calculation yields the following. (Note: the srpSalt is normally generated randomly, but for illustrative purposes, here we used fixed pre-calculated values).

- srpSalt (hex string): 00f1000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 000000000000009b

- x (internal, as a hex string): ffd36e11f577d312892334810d55089cb96c39443c255a9d85874bb6df69a537

- x (internal, as decimal integer): 11571334079566

92128319718196619842967585739396 25477265918747447380376082294071

- v (internal, decimal integer): 710597

15947322363168818619231596014948 50266475387982152630667264830126 91363325468391002539838039127254 13731153916626297948231925131054 77620430120387238383382529286340 32606803605961340789655696705692 35971894130915251144385164054999 20023879039952438012163402227132 85297349371740668115032272229446 78351915275352511787735824142082 28132003206595132571178470786998 71417330468650192650539261877568 70781628009053137574167426864838 84981432162129791810924115157063 80745962226827721585324849766449 08876686423788254204401136102193 24427662561738518576134929894589 97367433462254526788221238212661 40913290180513540399852050747986

- srpVerifier (hex string):

00901a4e05a7986c fafe2c80993f6e21 847d38b8b9168065 149480722d008c9a c5fe418d799d03c2 b1c26db2afcd4513 0a0601d310faa060 cc728888aba130a1 7d855773107ecc92 f31ea3a3838bc727 77fc26420ed59918 298583d15640b965 939dd6967e943bd6 ed846dbbb18885c7 4f6e9370e4eeecc4 c8e2a648850cf2ba 5baab18888b433c4 b0bd8891eeffe16c c022a098284696bc 3a81e735a1a2a371 62f62b980879bbd4 03ae55548b9feeec b18bf0740f0d078a 435fedb5324d630e 8a14fed435fbb5ea 4b6e94b8b129799d 2a0991671a67be34 149dc5e94a4a3d05 749fc3b9e1a53282 96b20a15348420be d2f28d2558cb4099 f30be8a7240c9252

The client sends srpSalt and srpVerifier to the server when it creates the account. It will also re-compute the 'x' value (as an integer) during sign-in. The server will convert the srpVerifier string back into an integer ('v') for use during its own sign-in calculations.

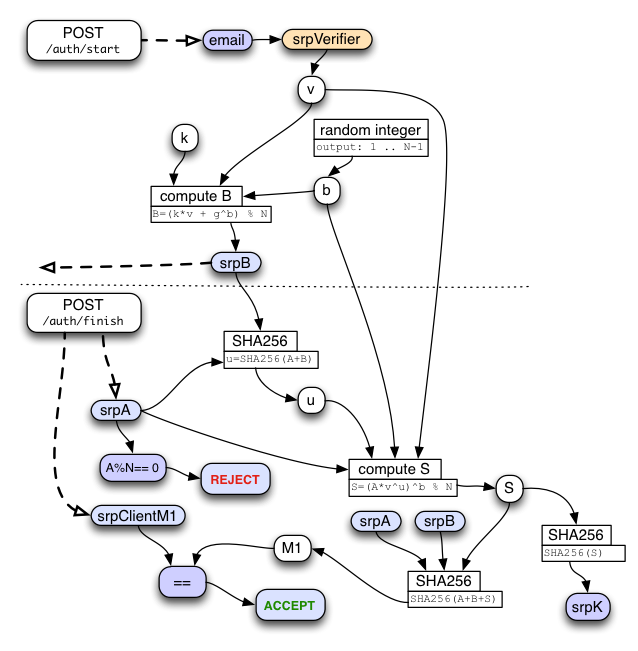

SRP Server-side Sign-In Flow

When the user connects a new device to their account, they use the getToken1() API to start the SRP protocol. This sends the account email address to the server. The server looks up the stored srpVerifier for this account, creates a random 'b' integer, performs some math to compute the "B" number, then converts B into a string known as "srpB". "srpB" is returned to the client, along with srpSalt and the key-stretching parameters. "b" and "srpB" are retained for the subsequent getToken2() call. Note that it is critical that the "b" integer remain secret on the server.

- b (hex integer, normally random but pre-calculated for this example):

00f3000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000020

- b (as decimal integer):

1198277 66042000957856349411550091527197 08125226960544768993643095227800 29105361555030352774505625606029 71778328003253459733139844872578 33596964143417216389157582554932 02841499373672188315534280693274 23189198736863575142046053414928 39548731879043135718309539706489 29157321423483527294767988835942 53343430842313006332606344714480 99439808861069316482621424231409 08830704769167700098392968117727 43420990997238759832829219109897 32876428831985487823417312772399 92628295469389578458363237146486 38545526799188280210660508721582 00403102624831815596140094933216 29832845626116777080504444704039 04739431335617585333671378812960

- srpB (hex string):

00857f70b197a6f3 f79c4270a41c581d 62c7ec7fc554c797 481d4b4075b06be3 df7f4f189e71fbec 08d1bcff8c5e4f74 65256cba8a78b725 daa0b9bddcbbea43 d916067b12c59aaf 4a9cdad53e08e4a5 770ea72287987302 2c5f5f608eb94795 710a907e1b425080 688d9e7790ce0781 6e6b2cdb9ad2c18f 60a2a5feb91b6da3 92579c5eb1e36f42 5b85c34085b216b9 7c4a3f7ffeb887c8 78ce0152d8be66eb 9c7a51abbae3b3f6 56c6e56d95d3e148 a23af3e9aaa54c72 cde19b58bdcbfb34 b9eb7f6dcbcd86e2 7e6221f6d3da2517 255088f5e7c408b3 7d6765120134b719 86287225d781c49a e5436b89525e17eb dcb8f3b7eb43163a cfb31c45a51a5267

Later, getToken2() will be called with the client's srpA string and its M1 key-confirmation string. srpA is combined with srpB to calculate the "u" integer. srpA is also turned into an integer and used to compute the shared-secret "S" integer. S is then used to compute the shared key "srpK", which is the output of the SRP process.

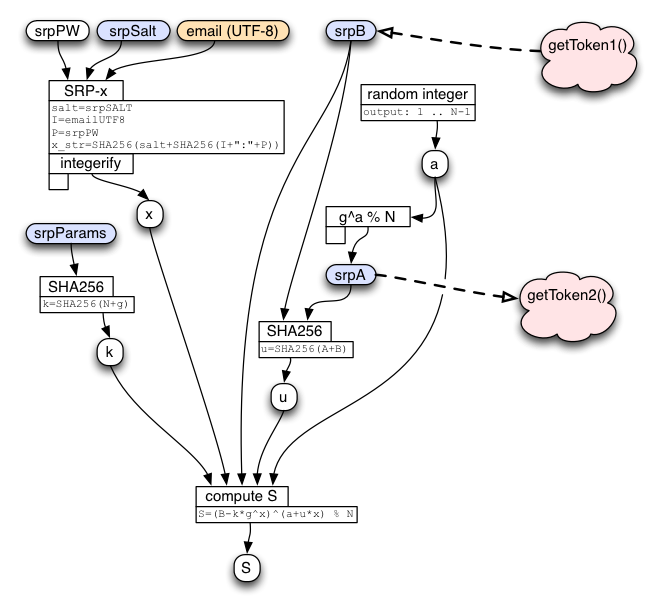

SRP Client Calculation

While the client is waiting for the response to getToken1(), it begins its key-stretching calculations. Everything else must wait until the response to getToken1() arrives, which includes the key-stretching parameters (which are retroactively confirmed), srpSalt, and the server's generated srpB value.

Once the client knows srpSalt, it computes the same "x" integer as it did in the middle of the srpVerifier calculation. It also converts srpB into an integer named "B". Then it creates a random "a" integer, uses it to compute the string "srpA", then combines srpA with the server's srpB to compute the "u" integer. It then combines the static "k", the password-derived "x", the combined "u", and the server's "B", together with some magic math, to derive the "S" integer. If everything went well, the client will compute the same "S" value as the server did. If not (the password was wrong, or the client is talking to a fake server that doesn't really know srpVerifier), then the two "S" values will not match.

(Again, it is critical that the client keep its "a" and "x" integers secret, both during and after the protocol run.)

- a (hex integer, normally random but pre-calculated for this example):

00f2000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0000000000000000 000000000000115c

- a (as decimal integer):

1193346 47663227291363113405741243413916 43482736314616601220006703889414 28162541137108417166380088052095 43910927476491099816542561560345 50331133015255005622124012256352 06121987030570656676375703406470 63422988042473190059156975005813 46381864669664357382020200036915 26156674010218162984912976536206 14440782978764393137821956464627 16314542157937343986808167341567 89864323268060014089757606109012 50649711198896213496068605039486 22864591676298304745954690086093 75374681084741884719851454277570 80362211874088739962880012800917 05751238004976540634839106888223 63866455314898189520502368799907 19946264951520393624479315530076

- srpA (hex string)

00f2a357d7da7132 1be6c070fb3a5928 8cec951cb13e7645 1f8c466ab373626a 7272dc1484c79ea3 cd1ea32e57fa4665 2e6450aa61ac5ee7 eac7a8c06c28ab19 5ccbe57500062c50 1a15fbb23a7f71b2 35448326af5e51c0 63f167378c782137 93dbc54efb32f204 de753d7a6b3d826d aaefc007d17862af 9b6a14e35f17f1eb 8b13c7b8ffa1f6f4 7b70d62bd0c351b4 7596b0b0abcba95c 2d731869ed6e4ec2 4ab90da8cb22e65d 256315ee84d8079b 4086d90c4e827b51 bb4e4d2d7b387da0 2e6b48904a3ba6d7 648a9bcdf3e9fc60 7cfba92f8eacae12 3ac45a79307cf3dd 281ed75a96c7de8f cd823f148dcc0634 9795f825fb029859 b963ab88320133de

- u (hex string)

610c6df1f495e429 8a2a59a0f5b00d47 ea2ed6ce2ccec8f7 ade158314a7bd794

- S (hex string)

009cc8da2f7a9501 5bc0091faa36d6ef ff52c33b924353e1 1de1d8e738654d6f 6a481003acb17cae 2ba2d4ae3fea8431 4c940397640fce92 d9153dffb7f3bd29 cbdb49e4ff0d26c4 67061337fd370851 4e3039d24cb54dc4 6420426b0daf7724 63fe06eb1521c7b0 96c4eeb6e5f9f739 49dcc74bc91baab8 398aff6df6735da2 c9486a645a20f2d7 d8f455a2bd226f21 e127f23e202b21fd d4ef64dc1a6740b6 fcd2a6b032fcb393 a2b9d97506b6fb89 5585d29173cc0e89 c3b3077ffa31215d b602b28364f81012 46ee9e8c47b63881 f3f867e67971825d f6a881d1142989ab cd4abba9c27ae529 c31be53f69966ccb 81f7660f95d5f8fc 45d052df3bcbb761

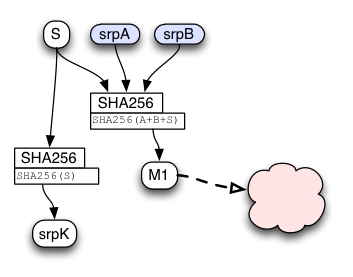

To safely tell if the "S" values match, both client and server combine srpA, srpB, and their (independently) generated "S" strings to form a string named "M1". The client sends M1 (along with srpA) in the getToken2() message. The server compares the client's copy of M1 against its own. If they match, the client knew the password and the server can safely respond with the encrypted account data. If they do not match, the client (or a man-in-the-middle attacker) did not know the password, and the client should increment a counter that can trigger defenses against online guessing attacks.

Both client and server also hash "S" into "srpK". This is the shared session key, from which specific message encryption and MAC keys are derived (as described below).

- M1 (hex string):

182ff26523922c52 559cab3cdfc89a74 c986b1d7504ea53d 11d9a204fc54449d

- srpK (hex string):

78a36d3e0df089e7 29a98dee3290fc49 64cd6ec96b771d6a bb6efe9181be868b

SRP Notes

The SRP "g" (generator) and "N" (prime modulus) should use the 2048-bit value from RFC 5054 Appendix A. Clients should not accept arbitrary g/N values (to protect against small primes, non-primes, and non-generators). In the future we might allow alternate parameter sets, in which case the server's first response should indicate which parameter set to use.

There are several places in SRP where integers (usually in the range 1..N-1) are converted into bytestrings, either for transmission over a wire, or to be passed into a hash function. The SRP spec is somewhat ambiguous about padding here: if the integer happens to be less than 2^2040, the simplest toString() approach will yield a *255* byte string, not a 256 byte string. PiCL consistently uses padding, so compatible implementations must prepend one or more NUL bytes to these short strings before transmission or hashing. The examples above were brute-forced to ensure that "srpVerifier", "srpA", "srpB", and "S" all wind up with leading zeros, to exercise the padding code in compatible implementations. If you are having problems getting your code to match these results, add some assertions to test that the stringified integers being put into hashes are exactly 256 bytes long.

The client does its entire SRP calculation in a single step, after receiving the server's "B" value. It creates its "A" value, computes the shared secret S, and the proof-of-knowledge M1. It sends both "A" and "M1" in the same message (getToken2).

The server receives "A" in getToken2, computes the shared secret "S", computes M1, checks that the client's M1 is correct, then derives the shared session key K. It then allocates a token (of the requested type) and encrypts kA+wrap(kB)+token as described below, returning the encrypted/MACed bundle in the response to getToken2.

Outstanding crypto questions:

- How exactly should the "a" and "b" integers be generated? The issue is of how much bias SRP can tolerate. Ideally these integers are uniformly distributed from 1 to N-1 (inclusive). The only way to obtain a purely uniform distribution from a source of random bytes is try-try-again: pick a (integral-number-of-bytes) number, compare it to the desired range, try again if it falls outside the range. If you get unlucky, this can take a lot of guesses, depending upon how close the range is to a power of two. ECDSA implementations tend to pick a number twice as long as the modulus and then modulo it down (rand(2^4096) % N), which yields a tiny fraction of a bit of bias. The cheaper approach is to do the same with a number of equal length (rand(2^2048) % N), which imposes more bias. Some SRP implementations appear to be satisfied by rand(2^256). We need more review here.

- The original SRP papers defined M1=H(A+B+S) as we use here, but other implementation (in particular RFC2945) uses a curious construct that includes the username, the salt, and an odd XOR combination of N and g. We need to decide what to use for M1.

getToken2

This method has two flavors, one for obtaining "signing tokens", the other for getting "reset tokens". TBD: either we'll have two different method names / API endpoints (getToken2Sign and getToken2Reset), or we'll pass an argument to a single "getToken2" method that indicates either "sign" or "reset". (using different endpoints would make it easier to monitor server load).

The client-side SRP calculation results in two values that are sent to the server in the "getToken2()" message: "srpA" and "srpM1". "A" is the client's contribution to the SRP protocol. "M1" is an output of this protocol, and proves (to the server) that this client knew the right password.

The server feeds "A" into its own SRP calculation and derives (hopefully) the same "S" value as the client did. It can then compute its own copy of M1 and see if it matches. If not, the client (or a man-in-the-middle) did not get the right password, and the server will return an error and increment it's "somebody is trying to guess passwords" counter (which will be used to trigger defenses against online guessing attacks). If it does match, then both sides can derive the same "K" session key.

The server then allocates a token for this device, and encrypts kA/wrap(kB)/token with the session key. The server returns a success message with the encrypted bundle.

Future variants (e.g. to fetch a third kind of token) might put additional values in the response to getToken2.

Decrypting the getToken2 Response

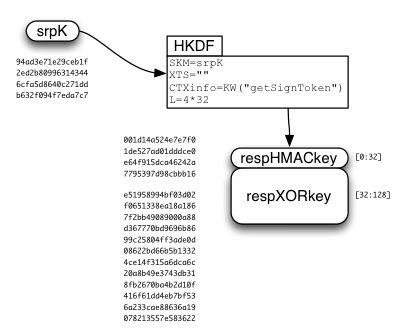

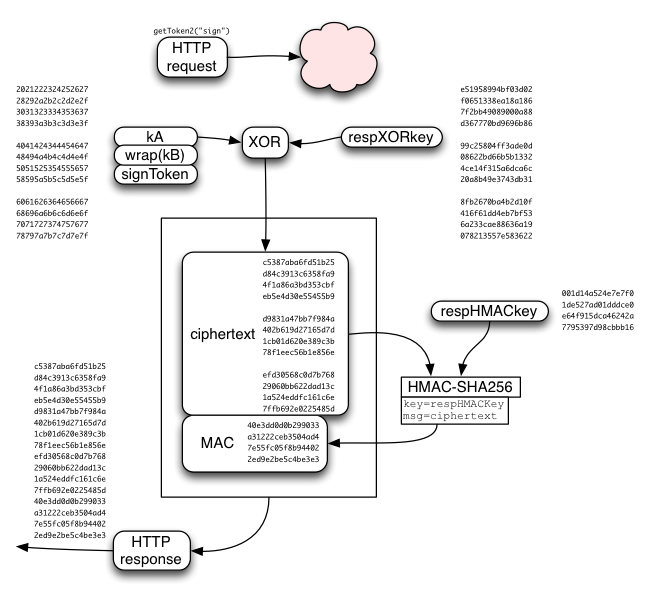

The SRP session key ("srpK") is used to derive two other keys: respHMACkey and respXORkey.

The respXORkey is used to encrypt the concatenated kA/wrap(kB)/token string, by simply XORing the two. This ciphertext is then protected by a MAC, using HMAC-SHA256, keyed by respHMACkey. The MAC is appended to the ciphertext, and the whole bundle is returned to the client.

The client recomputes the MAC, compares it (throwing an error if it doesn't match), extracts the ciphertext, XORs it with the derived respXORkey, then splits it into the separate kA/wrap(kB)/token values.

Since the kA/wrap(kB)/signToken response is so similar to the kA/wrap(kB)/resetToken response, the same code can be used to check+decrypt both. However remember that the respXORkey/respHMACkey is derived differently for each (using different "context" values).

Signing Certificates

The current stub just submits (cert, signToken), and gets back a signed certificate. This will be replaced soon.

(TBD, future protocol)

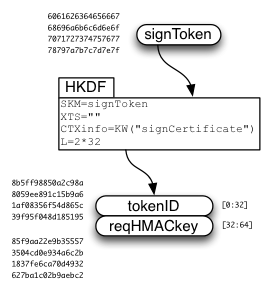

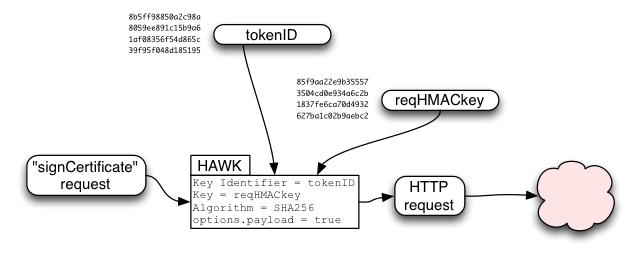

The Sign Token is used to derive two values:

- tokenID

- request HMAC key

The requestHMACkey is used in a HAWK (https://github.com/hueniverse/hawk/) request to provide integrity over the "signCertificate" request. It is used as credentials.key, while tokenID is used as credentials.id . HAWK includes the URL and the HTTP method ("POST") in the HMAC-protected data, and will optionally include the HTTP request body (payload) if requested.

For signCertificate(), it is critical to enable payload verification by setting options.payload=true (on both client and server). Otherwise a man-in-the-middle could submit their own public key, get it signed, and then delete the user's data on the storage servers.

HAWK provides one thing: integrity/authentication for the request contents (URL, method, and optionally the body). It does not provide confidentiality of the request, or integrity of the response, or confidentiality of the response.

For signCertificate(), we do not need request confidentiality or response confidentiality, since the client's pubkey and the resulting certificate will both be exposed over a similar SSL connection to the storage server later. And it is sufficient to rely on the response integrity provided by SSL, since the client can verify the returned certificate for itself.

Resetting the Account

The current stub just submits (newPassword, wrap(kB), resetToken). This will be replaced soon.

resetAccount() needs request confidentiality, since the arguments include the newly wrapped kB value and the new SRP verifier, both of which enable a brute-force attack against the password. HAWK provides request integrity. The response is a single "ok" or "fail", conveyed by the HTTP headers, so we do not require response confidentiality, and can live without response integrity.

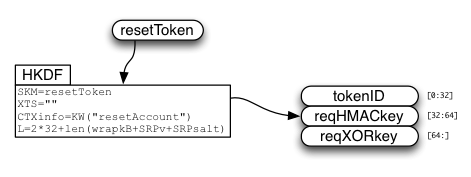

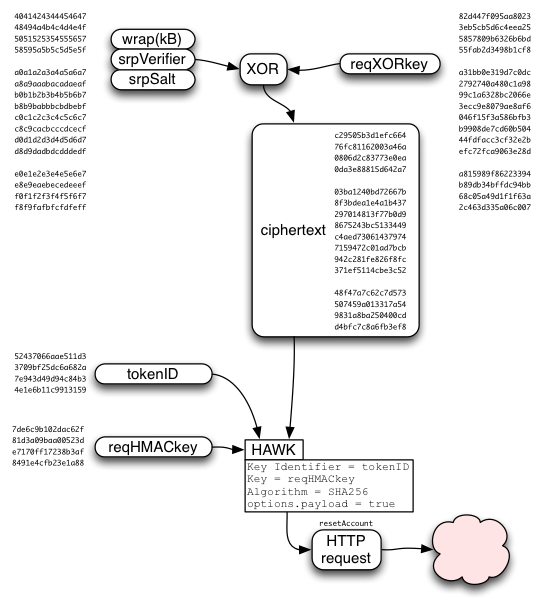

So the single-use resetToken is used to derive three values:

- tokenID

- request HMAC key

- request XOR key

The request data will contain kA, wrap(kB), and the SRP verifier, concatenated together. The first two pieces are fixed-length. We generate enough reqXORkey bytes to cover all three values.

The request data is XORed with requestXORkey, then delivered in the body of a HAWK request that uses tokenID as credentials.id and requestHMACkey as credentials.key . Note: it is critical to include the request body in the HAWK integrity check (options.payload=true, on both client and server), otherwise a man-in-the-middle could substitute their own SRP verifier, giving them control over the account (access to the user's class-A data, and a brute-force attack on their password).

Creating the Account

To create the account in the first place, the client starts with email+password, then does the following steps:

- decide upon stretching parameters (perhaps consulting the keyserver for recommendations, but imposing a minimum strength requirement)

- decide upon a stretchSalt (remembering this should be unique, but is not secret)

- decide upon SRP parameters (generally fixed)

- perform key-stretching, derive masterKey

- create kA and kB, combining entropy from the local OS with more from the keyserver's getEntropy()

- create wrap(kB), using unwrapKey (derived from masterKey)

- create srpVerifier, using srpPW and the SRP parameters

- deliver many values to the keyserver: parameters for stretching and SRP, kA, wrap(kB), and the srpVerifier

Crypto Notes

Strong entropy is needed in the following places:

- (client) initial creation of kA and kB

- (client) creation of private "a" value inside SRP

- (server) creation of private "B" value inside SRP

- (server) creation of signToken and resetToken

On the server, code should get entropy from /dev/urandom via a function that uses it, like "crypto.randomBytes()" in node.js or "os.urandom()" in python. On the client, code should combine local entropy with some fetched from the keyserver via getEntropy(), to guard against failures in the local entropy pool. Something like HKDF(SKM=localEntropy+remoteEntropy, salt="", context=KW("mergeEntropy")).

An HKDF-based stream cipher is used to protect the response for getToken2(), and the request for resetAccount(). HKDF is used to create a number of random bytes equal to the length of the message, then these are XORed with the plaintext to produce the ciphertext. An HMAC is then computed from the ciphertext, to protect the integrity of the message.

HKDF, like all KDFs, is defined to produce output that is indistinguishable from random data ("The HKDF Scheme", http://eprint.iacr.org/2010/264.pdf , by Hugo Krawczyk, section 3). XORing a plaintext with a random keystream to produce ciphertext is a simple and secure approach to data encryption, epitomized by AES-CTR or a stream cipher (http://cr.yp.to/snuffle/design.pdf). HKDF is not the fastest way to generate such a keystream, but it is safe, easy to specify, and easy to implement (just HMAC and XOR).

Each keystream must be unique. SRP is defined to produce a random session key for each run (as long as at least one of the sides provides a random ephemeral key). We define resetToken to be a single-use randomly-generated value. Hence our two HKDF-XOR keystreams will be unique.

A slightly more-traditional alternative would be to use AES-CTR (with the same HMAC-SHA256 used here), with a randomly-generated IV. This is equally secure, but requires implementors to obtain an AES library (with CTR mode, which does not seem to be universal). An even more traditional technique would be AES-CBC, which introduces the need for padding and a way to specify the length of the plaintext. The additional specification complexity, plus the library load, leads me to prefer HKDF+XOR.