Learning/WebLiteracyStandard/Legacy/WebLiteraciesWhitePaper

This is a legacy page for reference purposes.

We're proposing a new Learning Standard for Web Literacy

Find out more >>>

Mozilla Web Literacies white paper

v0.91 (release candidate)

Working towards a framework to understand the skills, competencies and literacies necessary to be a Webmaker.

Authors: Mozilla Learning Team and you!

Contact: Doug Belshaw: doug@mozillafoundation.org / @dajbelshaw

Short URL for sharing: http://mzl.la/weblit

Who is this for?

The Web is for everyone so, in essence, this Web literacies paper is also for everyone. It is, however, likely to be of particular use and value to educators and academics looking for a reference point and framework to help develop Web literacies in themselves and others.

When we mention ‘we’ in this white paper we’re talking about not only about Mozilla, but the community of people who believe in Constructivism, who believe in Connected Learning, and who believe in learning through making and doing. In other words, ‘we’ means ‘you’ as much as ‘us’! We’re people who believe in the practical application of knowledge through project-based and interest-based learning.

To help make the following a bit more tangible, let’s consider three scenarios:

- Leo, 15, is interested in expanding his understanding of coding, but more than anything he wants to make some cool stuff. He visits the Mozilla Webmaker site to make some projects and earn some badges. Then he adds these badges to his resumé to represent his new-found skills. Leo wants to connect with other youth interested in tech, so he joins a CoderDojo meetup in New York. He also attends a local hackjam and likes the group there after which he becomes a member and takes free HTML classes every Monday.

- Martha, 46, has been teaching for twenty years; she is invested in helping her students learn skills that are both current and relevant. A recommendation from a colleague tips her off to Mozilla’s Webmaker site. There she learns about Webmaking for the first time. While she’s on the site she finds curriculum to use in her classroom as well as a global community of innovative teachers with whom she can share ideas.

- Abdullah, 24, runs a small nonprofit start-up aimed at helping kids learn to code. He's a member of Hive London and is searching for activities to keep the kids who come along to his weekend workshops engaged. Abdullah creates a few projects that he can promote to a wider audience through the Mozilla Webmaker site.

What these three examples have in common is an individual with an interest, a practical need, and a desire to connect to others. We’ll return to Leo, Martha and Abdullah later to breathe life into some of the more abstract concepts in this white paper.

What are we talking about?

Before we can talk about Web Literacies in any detail we need to make sure we're clear what we mean when we say the 'Web'. Culturally speaking, the Web is the world’s largest public resource and (we believe) one of the greatest drivers of happiness and human flourishing the world has ever seen.1

The web is a system of interlinked documents and resources accessed via the Internet. On a slightly more technical level the Web is short for the World Wide Web (WWW) and is dependent upon the Internet. The Web and the Internet are often confused and conflated. As a global network of computer networks, the Internet can be used to access non-Web services such as email and Internet Relay Chat (IRC). The Web, meanwhile, is a 'layer' of interlinked hypertext documents. These documents tend to take the form of Web pages and can be accessed through Web browsers. These Web pages (collectively known as websites) tend to contain multimedia elements such as images, audio and video.

The open Web has enabled a dramatic increase in everyday access to information. Just as importantly it has facilitated new ways for people and communities to connect. In fact, it has allowed communities to form that never before would have come together. Many of these communities want to learn things together and achieve new skills using the Web as a platform. This makes being able to use the Web effectively relevant to everyone: developers, teachers, doctors, construction workers and many more, especially learners of any kind. We feel there is a new necessary set of literacies for modern citizens - Web literacies - that prepare them to effectively use the web to get information, connect with others and express themselves.

Literacy isn’t just about reading, but about writing too. When we think about literacies on the Web it’s important to go beyond just the differences between paper and screen. Those differences, such as the hypertextuality of the Web, are certainly important. But mastering these differences does not automatically lead to fluent use of the Web. Being Web literate means not only being able to read the Web but also having the ability to ‘write’ it.

Writing the Web - creating pages, documents and multimedia assets - means understanding the building blocks of the Web. As Mitchell Baker (Chairperson of Mozilla) says, we want to move beyond ‘elegant consumption’ towards creating a generation of Webmakers. We’re not talking about everyone becoming a fully-fledged programmer, but we do believe that everyone should have the skills, competencies and literacies to be able to tinker and make things with and on the Web. This is what Martha, the teacher in our example above, wants to help her students learn. She wants them to be able to make parts of the Web as well as consume them.

Although a knowledge of the physical makeup of the internet is necessary at some level, we’re primarily interested in the Web as accessed through a browser. We recognise that there are ‘Pre-Beginner’ skills such as identifying a Web browser’s address bar, using copy/paste functions, and entering the URL of a site directly (rather than searching). Likewise, there’s ‘Advanced’ skills such as code workflows and server-side technologies that go beyond what we’re talking about here. Both ‘Pre-Beginner’ and ‘Advanced’ skills are currently out of scope for this white paper. We’re focusing on the kinds of skills that Abdullah might teach at his weekend sessions, or Leo might learn at his weekly HTML classes.

Why are we talking about this?

We live in a networked economy at a time of accelerating change. As Duke University Professor Cathy Davidson has noticed, this means we need new literacies, new skills:

[O]ur world changed in April 1993 when the Mosaic 1.0 browser was released to the general public. We need new forms of education. We need to reform our learning institutions, concepts, and modes of assessment

for our age. Now, anyone with access to the World Wide Web can go far beyond the passive consumer model to contribute content on the Web. We can customize and remix, alone or in collaboration with others, located anywhere on the Web. That Do-It-Yourself potential for connected, participatory, improvisational learning requires new skills, what many are calling new “literacies.”

(Davidson, 2012)

As set out in the Mozilla Manifesto we believe that the Web is a resource to be protected; one to be co-created, not merely co-consumed. To create things with and on the Web means being able to both read and write it. In other words, to be Web literate, “we must learn not just how to use programs but how to make them” (Rushkoff, 2010).

The Web is becoming the world’s second language, and a vital 21st century skill. Digital literacy today is as important as reading, writing and arithmetic. Mozilla believes it’s crucial that people develop the skills they need to understand, shape and actively participate in that world, instead of just passively consuming it.

We want to help create a Web literate planet. We want to teach people about the Web through the Web, moving them from consuming it to making it as a means of self-expression. We want to create a generation of people who know how the Web works and can remix it. We also want to empower educators, those who want to teach other people about the Web.

Mozilla’s work is underpinned by a philosophy that we learn best through doing and making. While our work is underpinned by the works of academics in related fields, we’re interested in practical action. We’re focused upon encouraging people to become experienced in writing parts of the Web and participating in online communities.

Learning by making and tinkering is not a new idea, nor is our belief in interest-based pathways for learning. These concepts are fundamental to the work of foundational thinkers such as Froebel, Montessori, Dewey, Thorndike, Vygotsky, Papert and Csikszentmihalyi (amongst many others). Learning theories such as Constructivism2 and Connectivism,3 influence our work around Web Literacies along with notions such as Flow states4 and the importance of a sense of play.

We’re putting these learning theories into action through the Webmaker tools we’re creating and through the badge system design accompanying our work in this area. By employing elements of games mechanics we are creating interest-based pathways through a series of (badged) challenges. These promote flow states through clear goals and immediate feedback. More about this can be found in the Webmaker badges section below.

What are Web literacies?

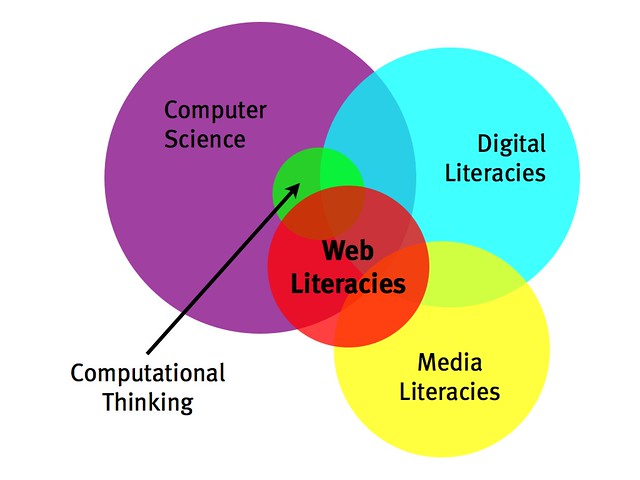

We’re currently working towards defining Web literacies as part of our work around Mozilla Webmaker. We understand Web literacies to be comprised of parts of digital literacies, media literacies, computational/algorithmic thinking and computer science. We’re also interested in newly-defined and emerging areas such as 'Hacker Literacies' (Santo, 2012).

The purpose of this white paper is to define and contextualise what we mean by Web literacies - and to inform activities for people wanting to work towards gaining those literacies. It also serves as a reference point for those who want to help create a generation of Webmakers, people who can ‘write’ as well as ‘read’ the Web.

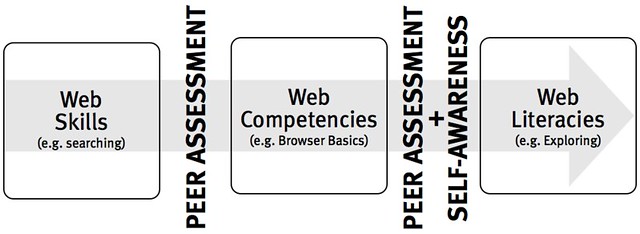

We see there being three steps to Web Literacies. First come Web Skills such as searching and using URLs appropriately. These are largely procedural, granular, and relatively easy to achieve.

Web Competencies is the next step, achieved by combining several related Web Skills. These are bundles of Web Skills for a particular purpose 'assessed' via a lightweight peer review system. Some Web Skills might be necessary for more than one of the Web Competencies. For example, identifying where to type to search in a particular browser would be a pre-requisite for both 'Search Engine basics' and 'Browser basics'.

Finally, Web Literacies consist of a range of these Web Competencies. For instance, 'Browser basics,' 'Search engine basics,' and 'Web mechanics' combine to form the 'Exploring' Web Literacies badge. In addition, some element of self-reflection is required here to realise that you’re now able to ‘Explore’ the Web at a beginner level.

Let’s look at Web Skills, Web Competencies and Web Literacies in a bit more depth.

Web Skills

By ‘skills’ we mean learned capacities to perform specific actions. Skills can be generic (transferable) or domain-specific. In terms of Web Skills the following may be helpful by way of illustration: a generic skill is understanding how code is structured; a domain-specific skill is how to use various elements of HTML (e.g. <p> and <h1> tags). In our earlier example, Leo learns both generic and domain-specific skills in his HTML classes.

Teachers in formal education are well aware that skills have objective thresholds. That’s to say the skills they teach young people are assessed by third parties (such as exam boards) against some kind of rubric. In a similar way to Scouting badges, the learner has to prove they have particular learned capacities in a given area. Likewise, the Mozilla Webmaker badges we’re developing require learners to demonstrate such capacities as they ‘level-up’.

Martha, our 46 year-old teacher, is interested in how the Web Skills developed via activities and projects on webmaker.org could be used in her lessons. She maps these skills onto her country’s national curriculum, sharing this on a wiki with other educators who can adapt it for their own purposes.

Web Competencies

By ‘competencies’ we mean collections of skills for pre-defined purposes. Web Competencies are bundles of Web Skills that allow individuals to ‘level-up’ in their knowledge, skills and understanding. Abdullah, for example, is interested in showing progression through the workshops and sessions he provides through his nonprofit start-up. He might decide to focus on teaching the skills young people need to gain the Web design basics competency badge.

Whether someone demonstrates a particular Web Competency depends on their displaying evidence of mastering certain Web Skills in that area. Building in an element of peer assessment at this stage ensures the evidence required stays fresh, current and relevant to what’s required to be effective on the Web today.

Returning to our learner scenarios, as Leo progresses in his knowledge, skills and understanding around HTML he realises he’s ready to submit some of his work for peer review. He places a mini-portfolio of his work online and asks the Webmaker community to look at it. Leo receives 13 up-votes and only 2 down-votes meaning he has received enough peer recognition to be awarded an HTML basics badge.

In the first instance the organisation awarding Webmaker badges will be Mozilla. As the ecosystem develops, however, we very much welcome and encourage other organisations to contribute tools, content and activities. These organisations will also be able to define the mix of skills that lead to competencies they wish to recognise and badge. Martha, for example, might want to tie the work she’s doing even more closely to the national curriculum or standards she is required to teach.

Web Literacies

At it’s most basic, ‘literacy’ is the ability to read and write something. As we’re focusing on Web Literacies the ‘thing’ that we’re reading and writing is the Web. In addition to this, however, as people become more literate we expect them to think critically and be able to look at the world from more than one perspective. For someone to be ‘literate’ they have to be aware that they are literate and be accepted within a wider community of literate peers.

Let’s take Leo as our example here. He continues attending his Monday HTML classes and starts tinkering with HTML and CSS at home as well. After a few months he gains Web Competencies badges in HTML basics, CSS basics and Web design basics. When a friend asks for help with a website she’s designing, Leo decides start an after-school interest group with her. Soon, he’s creating ‘howto’ videos for the benefit of those in his nascent community, while she’s working towards Javascript basics to be able to teach others. Teaching something you’ve recently learned yourself forces self-reflection on your own knowledge, skills and understanding.

Literacy is a condition to be obtained not a threshold to cross. We want people not only to self-identify as Webmakers but demonstrate the knowledge, skills and understanding required to be part of one or more web communities. We’re still in the process of defining the process by which individuals obtain Web Literacies badges, but they’ll contain both elements of peer assessment and self-reflection.

Towards a framework for Web Literacies

We’re approaching Web Literacies in a bottom-up way, identifying the skills necessary to be able to use and make aspects of the web. We’ve crowdsourced these skills both internally within Mozilla and externally through various channels. We invite other organisations and communities to get involved. The skills we’ve crowdsourced combine into competencies that reside broadly in one of four areas of Web Literacies:

- Exploring - I navigate the Web while learning, questioning and evaluating what it has to offer.

- Creating - I create things with the Web and solve problems while respecting the work of others.

- Connecting - I communicate and participate appropriately in one or more Web communities.

- Protecting - I protect the Web as a public resource for free expression.

The grid below is a flexible framework that we’re using to inform our work around Webmaker badges. It’s not fixed for all time, but will develop with the Web - along with input from other interested parties.

Web Skills / Competencies / Literacies grid

| EXPLORING | CREATING | CONNECTING | PROTECTING |

| BEGINNER | |||

| Browser basics (e.g. URLs, copy/paste) |

HTML basics (e.g. adding images, linking) |

Participation (e.g. etiquette, curation) |

Privacy (e.g. cookies, privacy controls) |

| Search engine basics (e.g. keyword search, filtering) |

CSS basics (e.g. fonts, positioning) |

Collaboration (e.g. co-creation, wikis) |

Security basics (e.g. HTTPS, password management) |

| Web mechanics (e.g. view source, hyperlinks) |

Web design basics (e.g. affordances of the Web, designing for audiences) |

Sharing (e.g. social networks, embedding) |

Rights online (e.g. copyright, open licensing) |

| INTERMEDIATE | |||

| Browser skills (e.g. cookie management, add-ons) |

Javascript basics (e.g. programming basics, javascript syntax) |

Contributing to Web communities (e.g. distributed working, collaborative curation) |

Identity (e.g. personal information curation, tracking management) |

| Credibility (e.g. trustworthiness of websites, evaluating information) |

Advanced Web design (e.g. responsive design, accessibility) |

Storytelling (e.g. multimedia, augmentation) |

Security & encryption (e.g. data protection, basic encryption) |

| Remixing (e.g. mashups, hackable games) |

Infrastructure (e.g. hosting, domains) |

Open practices (e.g. open standards, open source) |

Legalese on the Web (e.g. privacy policies, terms of service agreements) |

As well as input from those currently making the Web with Mozilla and other organisations, this grid is informed by the work of Beetham & Sharpe (2009), Belshaw (2011), Davidson (2011), Jenkins (2009), Rheingold (2012), Udell (2011), and Wing (2006). Their ideas around participatory culture, digital literacies and computational thinking can be found in, for example, the abstraction required for getting started with programming, understanding the architectures of participation involved in tech communities, the creativity and communication inherent in Web design, and getting involved in remix culture.

Webmaker badges

In order to provide ways to ‘level up’ in being able to make aspects of the Web we’re currently working on a series of Webmaker badges. These are allied to our work around Open Badges - a new way to get recognition for skills and achievements and display them across the Web.

We see badges as a way to connect tools with learning experiences, as well as learners to other community members. Our target audience are amateurs who have something to say and want to learn how to tinker and create with the Web in ever-more powerful ways. They provide a way for Leo to demonstrate his learning, for Martha to motivate her students, and for Abdullah to provide structure to his weekend workshops.

An example of our thinking (still a work in progress) is the HTML basics badge. This is a Web Competency badge made up of a collection of Web Skills such as:

- Clean Coder - fixing / adding clean code

- Optimizer - cleaning up code / deleting unnecessary code

- Code Whisperer - adding explanatory code comments

- Code Builder - writing clean code

- Editor - fixing / adding heading <h1>, paragraph <p>

- Image Maker - fixing / adding image

- 3DI Visioneer - fixing / adding html <div>

- A-Lister - fixing / adding html <ol> <li>

- Media Maker - fixing / adding media <iframe>

- Audio Maker - fixing / adding audio

- Hyperlinker - fixing / adding hyperlink

- Quick Fixer - fixing syntax errors / adding appropriate opening and closing tags

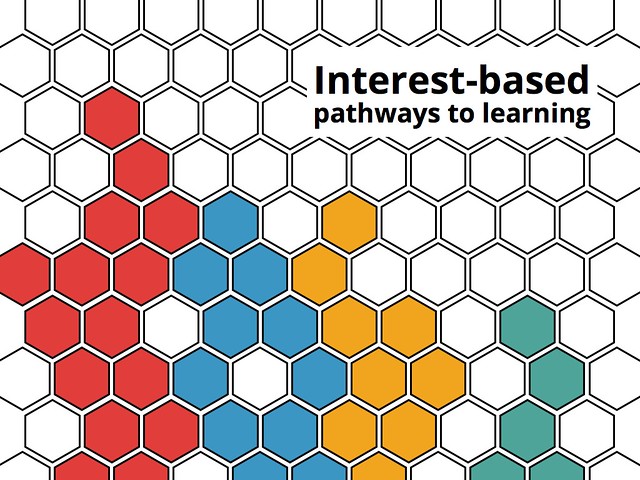

As we’re providing interest-based pathways the idea is that while a certain number of Web skills would have to be gained to achieve the HTML basics badge, there’s no requirement to gain every skill. An example of some interest-based pathways can be seen below. The coloured hexagons indicate badges that have been gained, with those remaining white being yet to achieve:

Levelling-up to a Web Competency badge requires the learner to complete at least the minimum number of Web Skills badges in that particular area. Some Web Skills badges will contribute to more than one Web Competency badge. In this case obtaining the 'Clean Coder', 'Hyperlinker, 'Quick Fixer', 'Image Maker', and 'Code Whisperer' Web Skills badges may mean you have enough badges to begin the levelling-up process towards 'HTML Basics'. Some of these badges (e.g. 'Hyperlinker') may also start you on the path towards other badges (e.g. 'Sharing'). In order to be issued a Web Competency badge, however, the learner must successfully pass peer-assessment of their work by those who already have that badge.

At the Web Literacies level the learner must have completed all of the Web Competencies badges in that area (Exploring/Creating/Connecting/Protecting). Then, in addition to peer assessment, the learner must complete some kind of self-reflective activity. This may be portfolio-based.

Conclusion

We believe that everyone should have the skills, competencies and literacies to be constructive and creative on the Web. While not everyone needs to be a fully-fledged programmer or Web designer, given the pervasiveness of the Web in our lives everyone certainly needs to feel like the Web is a medium to be written and made as well as one to be read and consumed.

The Web Literacies framework, the interest-based pathways, and the badges we propose enable learners to level-up in their knowledge and skills of the Web. Our aim is to create a generation and a community of Webmakers who feel empowered to use the Web in their everyday lives.

This Web Literacies white paper is the beginning of a conversation: we’re not attempting to create a ‘canon’ of knowledge or skills. Instead, we’re looking to create a flexible framework of Web Skills, Competencies and Literacies that can evolve along with the Web itself. We’d very much like it if you could join us in that journey.

References

Beetham, H. & Sharpe, R. (2009) ‘Responding to Learners’, Keynote presentation at the JISC Online Conference 2009, available at: http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/elearningpedagogy/elpconference09/programme/respondinglearners.aspx (accessed 23 October 2012)

Belshaw, D.A.J. (2011) ‘What is ‘digital literacy’? A Pragmatic investigation’, (unpublished doctoral thesis), Durham University, available at: http://neverendingthesis.com (accessed 14 October 2012)

Davidson, C.N. (2011) Now You See It: How Technology and Brain Science Will Transform Schools and Business for the 21st Century, London: Viking Books

Davidson, C.N. (2012) ‘Why We Need a 4th R: Reading, wRiting, aRithmetic, algoRithms’, DMLcentral, available at: http://dmlcentral.net/blog/cathy-davidson/why-we-need-4th-r-reading-writing-arithmetic-algorithms (accessed 18 September 2012)

Davidson, C.N. & Goldberg, D.T. (2009) ‘The Future of Learning Institutions in a Digital Age’ (The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Reports on Digital Media and Learning), Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Jenkins, H. (2009) Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century (The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Reports on Digital Media and Learning), Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Rheingold, H. (2012) Net Smart: How to Thrive Online, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Rushkoff, D. (2010) Program or be Programmed: Ten Commands for the Digital Age, London: OR Books

Santo, R. (2012) ‘Hacker Literacies: Synthesizing Critical and Participatory Media Literacy Frameworks,’ International Journal of Learning and Media, 3:3, pp.1-5

Udell, J. (2011) ‘Seven Ways to Think Like the Web’, Weblog, available at: http://blog.jonudell.net/2011/01/24/seven-ways-to-think-like-the-web/ (accessed 17 October 2012)

Wing, J.M. (2008) ‘Computational Thinking and Thinking about Thinking,’ Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society, 366, pp.3717-3725

Footnotes

1 See Mozillian Gervase Markham’s post: http://blog.gerv.net/2012/07/mozilla-an-ethical-career

2 Constructivism is, broadly speaking, a learning theory that focuses upon experiential learning, self-direction, creativity, first-hand experience. It posits learning as an active, social process.

3 Connectivism is a theory of learning that sees learning as a process of practice and reflection. It allows for knowledge to reside in non-human actors and sees learners as 'nodes on a network'.

4 A state of ‘Flow’ as defined by Csikszentmihalyi, includes an activity with clear goals, clear and immediate feedback, and with a good balance between (perceived) challenges and (perceived) skills.