Abstract Interpretation

This is a work in progress to explain the static program analysis technique of Abstract Interpretation, which is basic background for using the Treehydra abstract interpretation libraries.

Background: Program Analysis

This is just some boring background material. Feel free to skip to Introduction on first reading.

Program analysis refers to algorithms for discovering facts about the behavior of programs. Examples include finding which variables are constant, whether null pointer errors can occur, or whether every "lock" operation is followed by exactly one "unlock". Program analysis is a basic technology with many applications, especially compiler optimizations, bug finding, and security auditing.

Program analysis has two major divisions: static analysis and dynamic analysis. Dynamic analysis basically means testing: you run the program on one or more test cases and observe its behavior. For example, you can run the program and see if you get any null pointer errors. The primary advantage of dynamic analysis is that you can get exact information about the program behavior, because you are actually running it. The disadvantage is that you get information only for the test inputs you provide, and only for the code paths exercised by those test inputs. Thus, dynamic analysis cannot prove that an optimization is safe or that a program is free of some class of security flaws.

The goal of static analysis is to solve this problem by attaining complete coverage of the program: using special algorithms to analyze the behavior over all possible inputs. The price is that the results are only approximate. (Discovering exact behavior for all inputs would solve the halting problem.) But the results only have to be approximate in one direction. That is, you can create a bug-finding analysis that has false positives (sometimes reports a bug where there is none) but does discover all bugs. And you can also create a version that has no false positives but might miss some real bugs. There is a lot of design freedom in how to approximate, and designing good approximations is a key part of the art of static analysis. The goal is to be precise where it counts for your results, but approximate elsewhere, so the analysis runs fast.

Introduction

Abstract interpretation is a basic static analysis technique. We will describe it informally, focusing on the ideas and practical applications, and leaving the mathematical underpinnings aside. We will focus on intraprocedural abstract interpretation, i.e., analyzing one function at a time, rather than analyzing the whole program together, because whole-program analysis is difficult to apply to a large codebase like Mozilla.

We're going to explain abstract interpretation using an example analysis problem called constant propagation. The goal is to discover at each point in the function whether any of the variables used there have a constant value, i.e., the variable has the same value no matter what inputs are provided and no matter what code path was followed. This analysis is used by compilers for the constant propagation optimization, which means replacing constant variables with a literal value. (This may save a load of the variable, and it also removes a use of the variable, which can enable other optimizations.)

Here is an example C++ function we want to analyze, with some comments showing constant variables.

int foo(int a, int b) {

int k = 1; // k is constant: 1

int m, n;

if (a == 0) {

++k; // k is constant: 2

m = a;

n = b;

} else {

k = 2; // k is constant: 2

m = 0;

n = a + b;

}

return k + m + n; // k is constant: 2

}

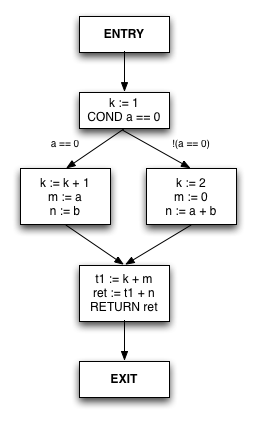

Control Flow Graphs

Abstract interpretation operates on a flowchart representation of the function called a control flow graph or CFG. Below is the CFG for the example function. This CFG is similar in flavor to the real GCC CFG, just with a few unimportant details removed.

It looks like a pretty normal flowchart. Some features to note:

- All possible control transitions are shown as explicit edges.

- Statements always have exactly one operation and at most one assignment. Temporary variables are added if necessary. This will really simplify our job: instead of handling every kind of C++ statement, we have only have to analyze these simple statements.

A little terminology:

- Each node is called a basic block, often abbreviated BB. The defining feature of a basic block is that there is a single entry point and a single exit--basic blocks are straight-line code.

- In different sources, statements may be called statements, instructions, triples (of a destination and up to 2 operands), quadruples or quads (counting the operator), or even tuples. We'll call them instructions, as that's the name used in Treehydra code.

- A program point is the (notional) point just before or after each instruction. The function has a well-defined state at program points, so our analysis facts will always refer to program points. E.g., at the program point just before 't1 := k + m', k is constant with value 2.

Concrete Interpretation

To explain abstract interpretation, we'll start with concrete interpretation, which is just the normal kind you are already familiar with. We'll use it to build up to abstract interpretation.

We could imagine trying to guess which variables are constant just by calling the function with different inputs, and finding which variables are constant over all those runs. Let's start by running with "a = 0, b = 7" and trace the run:

(instruction) (interpreter state after instruction) ENTRY a = 0, b = 7 k := 1 a = 0, b = 7, k = 1 COND a == 0 (TRUE) k := k + 1 a = 0, b = 7, k = 2 m := a a = 0, b = 7, k = 2, m = 0 n := b a = 0, b = 7, k = 2, m = 0, n = 7 t1 := k + m a = 0, b = 7, k = 2, m = 0, n = 7, t1 = 2 ret := t1 + n a = 0, b = 7, k = 2, m = 0, n = 7, t1 = 2, ret = 9 RETURN ret EXIT

So k = 2 just before its use in 't1 := k + m'. We can run with many other inputs and get the same result. But testing can never tell us that k = 2 for all inputs. (Well, actually it can, but only if you can run <math>2^64</math> test cases.)

Approaching Abstract Interpretation

But if you look at the function, you can see that for k, there are really only two important cases: a == 0, and a != 0, and b doesn't matter. So let's (on paper) run two tests: one with input "a = 0, b = ?" and the other with "a = NZ, b = ?", where NZ means "any nonzero value" and ? means "any value". First, a = 0:

(instruction) (interpreter state after instruction) ENTRY a = 0, b = ? k := 1 a = 0, b = ?, k = 1 COND a == 0 (TRUE) k := k + 1 a = 0, b = ?, k = 2 m := a a = 0, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0 n := b a = 0, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0, n = ? t1 := k + m a = 0, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0, n = ?, t1 = 2 ret := t1 + n a = 0, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0, n = ?, t1 = 2, ret = ? RETURN ret EXIT

It looks pretty much like the concrete case, except that we now have some abstract values, NZ and '?', that represent sets of concrete values.

We also have to know what operators do with abstract values. For example, the last step, "ret := t1 + n", evaluates to "ret := 2 + ?". To figure out what this means, we reason about sets of values: if '?' can be any value, then 2 + '?' can also be any value, so 2 + '?' -> '?'.

The other test is "a = NZ, b = ?":

(instruction) (interpreter state after instruction) ENTRY a = NZ, b = ? k := 1 a = NZ, b = ?, k = 1 COND a == 0 (FALSE) k := 2 a = NZ, b = ?, k = 2 m := 0 a = NZ, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0 n := a + b a = NZ, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0, n = ? t1 := k + m a = NZ, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0, n = ?, t1 = 2 ret := t1 + n a = NZ, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0, n = ?, t1 = 2, ret = ? RETURN ret EXIT

At this point, we've tested with every possible input, and we've tested every path, so our results are complete. This proves that k = 2 is in fact always true just before "t1 := k + m".

We're definitely getting somewhere, but the procedure we just followed doesn't generalize. We knew exactly what abstract values to use for the test cases, but that was only because this was a simple function and we could see that by hand. This won't work for complicated functions and it's not automatic. We need to make things simpler.

Another problem is that we are analyzing each path through the function individually. But a function with <math>k</math> if statements can have up to <math>2^k</math> paths, and a function with loops has an infinite number of paths. So on real programs, we'll experience path explosion and we won't get complete coverage.

Abstract Interpretation by Example

One problem with our first approach to abstract interpretation was that we don't know how to pick what sets abstract values to use for input test cases. So let's not. Instead, let's just do one test with any input at all: "a = ?, b = ?":

(instruction) (interpreter state after instruction) ENTRY a = ?, b = ? k := 1 a = ?, b = ?, k = 1 COND a == 0

Now what? We have no information about a, so we don't know which branch to take. So let's do both. First, the true case:

(instruction) (interpreter state after instruction)

a = ?, b = ?, k = 1

k := k + 1 a = ?, b = ?, k = 2

m := a a = ?, b = ?, k = 2, m = ?

n := b a = ?, b = ?, k = 2, m = ?, n = ?

Then, the false case:

(instruction) (interpreter state after instruction)

a = ?, b = ?, k = 1

k := 2 a = ?, b = ?, k = 2

m := 0 a = ?, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0

n := a + b a = ?, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0, n = ?

At this point, the two execution streams rejoin. We could just keep running the streams separately, but we know that will lead to path explosion in general. So instead, let's merge the streams by merging the states. We need a single interpreter state that covers both of these states:

a = ?, b = ?, k = 2, m = ?, n = ?

a = ?, b = ?, k = 2, m = 0, n = ?

We can get it by merging the variables individually. As before, we use set reasoning. For example, with k, we say, k is 2 on the left and on the right, so k = 2 in the merged state. With m, m could be anything if coming from the left, so even though it must be 0 if coming from the right, m could be anything in the merged state. The result:

a = ?, b = ?, k = 2, m = ?, n = ?

We can continue executing in one stream:

t1 := k + m a = ?, b = ?, k = 2, m = ?, n = ?, t1 = ? ret := t1 + n a = ?, b = ?, k = 2, m = ?, n = ?, t1 = ?, ret = ? RETURN ret EXIT

And we get the answer we wanted, k = 2. The key ideas were:

- "Run" the function using abstract values as inputs.

- An abstract value represents a set of (concrete) values.

- At a control-flow branch, go both ways.

- At a control-flow merge, merge the state.

Notice that this time, we didn't have to divide up states at the start, we just started with no knowledge, which is perfectly general. Also, because we rejoin execution streams, in a loop-free method, we only have to interpret each instruction once, so we have completely solved the path explosion problem. (We haven't tried loops yet, and they are a bit harder--they require us to analyze statements more than once, but only finitely many times.)