Webmaker/WebLiteracyMap/v2/research

Research from academic journals, blog posts, and elsewhere to inform v2.0 of Mozilla's Web Literacy Map.

2014

This article focuses on users of the web being able to assess the credibility of information:

"There seems to be a pressing need to develop a “web literacy” approach especially with the emergence of technologies like social software, wikis, blogs, open source systems and what is known as the Web 2.0 movement. Web literacy, a term first coined by Sorapure, Inglesby and Yatchisin (1998), has been defined as “an ability to recognize and assess a wide range of rhetorical situations and an attentiveness conveyed in a source’s non-textual features. Teaching such a literacy means supplementing the evaluative criteria traditionally applied to print sources with new strategies for making sense of diverse kinds of texts presented in hyper textual and multimedia formats” (Sorapure, Inglesby and Yatchisin, 1998)."

Keshavarz, H. (2014). How Credible is Information on the Web:

Reflections on Misinformation and Disinformation. Infopreneurship Journal, 1(2), 1-17.

2013

The 'specific skills' required for the web are discussed in this article, but the authors only focus upon navigation and credibility:

"Web literacy refers to the skills needed for successful web navigation Texas Journal of Literacy Education (November, 2008). Online reading requires specific skills, and these skills are often referred to by educators in K- 12 settings as web literacy skills. Classroom practices often involve research and “the rules of research have changed with society’s move from paper to digital information” (November, 2008, p. 6). Web literacy may fit under the umbrella of New Literacies in that it relates directly to skills needed to locate information accurately and effectively. Web literacy is also reflective of digital literacies, as it is a term used to explain knowledge an individual needs to find information, to examine content, to find out who published a Web site, and to see who is linked to a site (November, 2008)."

Pilgrim, J. & Martinez, E.E. (2013). Defining Literacy in the 21st Century:

A Guide to Terminology and Skills. Texas Journal of Literacy Education, 1(1), 60-69.

'Web literacy' in this article means effectively navigating the web:

"The two terms that seem most practitioner-friendly are web literacy and digital literacy. Web literacy, as the term implies, describes a user’s Internet navigation skills as well as critical thinking skills required to evaluate online information. This term is not as broad as digital literacy, but the skills provide teachers with concrete ways to help students search for accurate and reliable information in a safe Internet environment (November, 2008). This type of information and support for teachers has enabled educators to develop curriculum for teaching literacy skills."

Pilgrim, J. & Martinez, E.E. (2013). Defining Literacy in the 21st Century:

A Guide to Terminology and Skills. Texas Journal of Literacy Education, 1(1), 60-69.

2012

Rafi Santo (involved in Mozilla's Hive networks) talks of 'hacker literacies' which seems to encapsulate more of what Mozilla means by 'web literacy' - but also goes beyond this:

"I define hacker literacies as empowered participatory practices, grounded in critical mindsets, that aim to resist, reconfigure, and/or reformulate the sociotech- nical digital spaces and tools that mediate social, cultural, and political participation. These “critical mindsets” include perceiving how values are at play in the design of these spaces and tools; understand- ing how those designs affect the behaviors of users of those spaces and tools; and developing empow- ered outlooks, ones that assume change is possible, in relation to those designs and rooted in an under- standing of their malleability. “Empowered participatory practices” include making transparent for others the effects of sociotechnical designs and the values at play therein, voicing alternative values for these designs, advocating and taking part in alternative designs when spaces and tools are misaligned with one’s values, and employing new media as a means to change those digital spaces and tools—whether on the social or technological level—via social or technological means (Santo, forthcoming)."

Santo, R. (2011). Hacker Literacies: Synthesizing Critical

and Participatory Media Literacy Frameworks. International Journal of Learning and Media, 3(3), 1-5.

New literacy researchers are fond of claiming that their favoured term subsumes other terms. Here, information literacy is said to encapsulate web literacy:

"Information literacy is about accessing and analyzing information, and Web literacy is a subset of information literacy which involves applying those skills online and being able to recognize obscured intent and pay attention to non-textual features (Burke, 2002; Kuiper, Volman, & Terwel, 2009; Sorapure, Inglesby & Yatchisin, 1998). In other words, Web users must sort through both textual and visual cues to determine the credibility of information online."

Pariera, K. L. (2012). Information Literacy on the Web: How College Students Use Visual

and Textual Cues to Assess Credibility on Health Websites. Communications in Information Literacy, 6(1), 34-48.

This article, while referencing some critique, cites Prensky's widely-discredited 'digital natives/immigrants' approach'. It seems to argue that intensity of the use of the web can be correlated with 'literacy':

"Apart from social networks, one can discern another element of the transition to this new Web era; that of the increased level of digital literacy among people. One can at this stage distinguish between people who grew up using the Web, the ‘digital natives’(Prensky, 2001) on the one hand, and ‘digital immigrants’ with increased digital literacy, potentially honed by higher involvement in the Web activity, on the other hand. The differences between natives and immigrants are a topic of debate (Bennett, Maton, & Kervin, 2008) but one could argue that, overall, there has been an increase in Web literacy levels, based on the high number of users and intensity of use."

Hall, W., & Tiropanis, T. (2012). Web evolution and Web science.

Computer Networks, 56(18), 3859-3865.

2011

This project for a M.Ed. dissertation focused on web literacy and discusses how difficult it is to teach the relevant skills in isolation:

"If we accept that literacy skills and practices are seen as social, cultural, political and economic, then Web literacy skills should be viewed in the same way."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria).

"According to Kuiper, Volman and Terwel (2009), Web literacy is a concept that is comprised of “a combination of various skills regarding the critical use of the Web for one‟s own purposes” (p. 669). Web literacy skills can be divided into three subcategories that including searching on the Web, reading on the Web, and evaluating on the Web (Kuiper, Volman, & Terwell, 2009)."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p2.

"Reece (2009) defined Web literacy as “the ability to access, analyze, and evaluate online information” (p. 21); but Web literacy is a complex set of skills unique to its environment and requires a more nuanced definition. Kuiper, Volman, and Terwel (2009) propose that Web literacy is “the ability to handle the Web critically” (p. 669). They include three skills within their definition of Web literacy: Web searching skills, which includes using appropriate key words, locating relevant information, and knowing different ways to locate information; Web reading skills, which is the ability to interpret the results of search engines (such as Google), understanding and using hypertext, and knowing which information to choose and which to disregard; and Web evaluating skills such as assessing the reliability and validity of sources and relating text images to various sites (Kuiper, Volman, & Terwel, 2009, pp. 669-670)."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p4.

"Many scholars argue that within the study of Web literacy there is no single approach, but rather multiple perspectives (Coiro, Knobel, Lankshear, Leu, 2009; Kuiper & Volman, 2009).

[...]

Gee (1992, 2002, 2003) argues that to understand learning as sociocultural one must know that the mind is social, learning is embedded in cultural practices, and meaning is always situated."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p5.

"Socio-cultural theorists view social practices as members participating within a particular community. Gee (1992) uses the term Discourse, with a capital „D‟ to identify social practices. Within each social practice or Discourse, there are ways of talking, reading, writing, thinking, valuing, and interacting. According to Gee (1992), each type of literacy practice within a Discourse has discourses. Therefore, to be literate in a Discourse one must be able to be competent in the various discourses of the practice. Further, to be a member within a Discourse one must participate in it, and learn from someone who is already considered an expert. These learnings must be scaffolded by more sophisticated others and the learner must be able to see when certain skills are useful and how to apply those skills (Gee, 1992; Vygotsky, 1978)."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p6.

"Gee (2003) claimed that “[l]iteracy in any domain is actually not worth much if one knows nothing about the social practices of which that literacy is but a part” (pp. 14-15). Lankshear and Knobel (2007) add that “[t]here is no practice without meaning, [j]ust as there is no meaning outside of practice” (p. 2). Hence, reading and writing will have no meaning if they are practiced outside of the social contexts in which people participate. Further, deeper meaning is given to a text when someone is a producer of a text within a social practice rather than just a consumer (Gee, 2003). By the same argument then, those who are producers within a social practice are also better consumers because they can read and understand the text of the social practice."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p7.

"According to Gee (2002), “[a]ny efficacious pedagogy must be a judicious mixture of immersion in a community of practice and overt focusing and scaffolding from „masters‟ or „more advanced peers‟” (pp. 125-126). Educators need to examine what students know and value in their specialist domains, and then build connections for learning. In terms of Web literacy, even if teachers are not experts in the function of technology, or technological devices, they are still the expert in helping students build critical habits of mind. Additionally, it is the role of the teacher to scaffold the learning of critical thinking skills and demonstrate how those skills can transfer across the various domains and Discourses in which learners participate."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p8.

"Lankshear and Knobel (2003, 2007) have expanded on the notion of „new‟ in new literacies. Originally, they defined new literacies simply as “literacies associated with new communications and information technologies” (2003, p. 25). However, the definition has continued to grow in order to separate „new‟ from traditional literacy practices. In a later article, Lankshear and Knobel (2007) submitted that new literacies do not include the ability to look up information online or write an essay on a word processor because those would be considered traditional literacy skills simply using a new tool to speed up the task. Rather, new literacies include both “new technical stuff” and “new ethos stuff” (Lankshear & Knobel, 2007, p. 7). “New technical stuff” is considered to be tools that enable people to perform and participate in different kinds of literacies. Each type of tool can be associated with their own set of beliefs, values, norms, and procedures."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p9.

"A 2009 article published in Career World discussed skills that students should not leave high school without and ranked “Web literacy” as number one (Reece, 2009). Reece (2009) defined Web literacy as “the ability to access, analyze, and evaluate online information” (p. 21); but Web literacy is a complex set of skills unique to its environment and requires a more nuanced definition. Kuiper, Volman, and Terwel (2009) propose that Web literacy is “the ability to handle the Web critically” (p. 669). They include three skills within their definition of Web literacy: Web searching skills, which includes using appropriate key words, locating relevant information, and knowing different ways to locate information; Web reading skills, which is the ability to interpret the results of search engines (such as Google), understanding and using hypertext, and knowing which information to choose and which to disregard; and Web evaluating skills such as assessing the reliability and validity of sources and relating text images to various sites (Kuiper, Volman, & Terwel, 2009, pp. 669-670)."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p10.

"Lankshear and Knobel (2007) summarize their concept of “new literacies” by claiming that,

[t]he more a literacy practice privileges participation over publishing, distributed expertise over centralized expertise, collective intelligence over individual possessive intelligence, collaboration over individuated authorship, dispersion over scarcity, sharing over ownership, [...] the more we should regard it as a “new” literacy."(p. 21)

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p11.

"The Web is a vast resource of information that has evolved and changed from its original forms. Scholars have used the terms Web 1.0 and Web 2.0 to distinguish the difference in the function and purpose of the Web. Greenhow, Robelia and Hughes (2009) examine how the Web has changed over the previous 10 years and how those changes have affected teaching and learning. The term Web 1.0 has been used to classify the “first generation web” (Greenhow et al., 2009, p. 247). Web 1.0 was viewed as a classroom resource that paralleled traditional classroom practices. Web 1.0 contained authentic knowledge compiled by experts in their fields, where users were solely consumers of information.

[...]

Over time, however, the Internet has continued to expand in function and purpose. With the increasing amount of information access and use, Web 2.0 became one of which users were not only reading, but were writing and composing as well (Greenhow et al., 2009, p. 247). Web 2.0 became a collaborative environment, one that was based on collective participation, and using the Web was more about producing than consuming. Greenhow et al. (2009) describe Web 2.0 as “knowledge [being] decentralized, accessible, and co-constructed by and among a broad base of users” (p. 247)."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p14-15.

"Fabos (2009) and Lankshear and Knobel (2003) argue that there is a need to understand how search engines work in order to better utilize them as information finding sources."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p16.

"An earlier article written by Coiro (2003) argued that online reading includes an expanded notion of offline literacies as well as new literacies, and stated that nonlinear hypertext, multiple-media texts, and interactive texts need their own set of skills for use. Sutherland and Smith (2002) similarly argued that the Web is non-linear, non-hierarchal, and non-sequential, therefore making literacy practices more complex."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p20.

"The first skill required for successful use of the Web is the ability to search and locate needed information. Henry (2006) argued that, “locating information is, perhaps, the most important function of reading on the Internet; [a]ll other decisions and reading functions on the Internet emanate from the decisions that are made during the search process” (p. 616)."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p21.

"Second, learning on the Web should be viewed as a new literacy, one that requires a more complex set of skills than traditional print text. The very nature of the Web does not demand that information be centred on one authoritative source. For educators it means that explicit instruction and structural support is needed to help students become more critically engaged when searching and locating information on the Web (Friedman & Heafner, 2007; Kuiper & Volman, 2009; Kuiper et al., 2009; MacGregor & Lou, 2006)."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p35.

"I spent much time trying to think of how I could scaffold Web literacy skills. After devoting considerable time to drafting ideas, I concluded that I could not break down each Web literacy skill individually."

Brown, A. (2011). Teaching web literacy in the age of new literacies (M.Ed. dissertation, University of Victoria). p65.

2010

2009

2008

2007

"A distinctive feature of today’s literacy scene is the extent to which, and the pace with which, new socially recognized ways of pursuing familiar and novel tasks by means of exchanging and negotiating meanings via encoded artefacts are emerging and being refined. Moreover, these new ways are being developed and matured as socially recognized patterns of engagement with a good deal of creative consciousness on the part of those who are developing and refining them. Much of this conscious creation and refinement is being done by ‘tech savvy’ people, many of whom are young. In light of this we find Scribner & Cole’s account of practice more useful than a number of more recent alternatives that have been advanced within literacy studies. Scribner & Cole put technology upfront in their account of ‘practice’. Subsequently, this visibility often slipped into the background as concepts of literacy practices increasingly centred on texts, and their linguistic-semiotic dimensions. We want to put the technology dimension of practices squarely back in the frame."

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2007). Researching new literacies: Web 2.0 practices and insider perspectives. E-learning, 4(3), 224-240.

"Second, encoding involves much more than ‘letteracy’. Encoding means rendering texts in forms that allow them to be retrieved, worked with, and made available independently of the physical presence of an enunciator. The particular kinds of codes employed in literacy practices are varied and contingent. In our view, someone who ‘freezes’ language as a digitally encoded passage of speech and uploads it to the Internet as a podcast is engaging in literacy. So, equally, is someone who photoshops an image, whether or not it includes a written text component."

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2007). Researching new literacies: Web 2.0 practices and insider perspectives. E-learning, 4(3), 224-240.

"Accordingly, we think of new literacies having new ‘technical stuff’ and new ‘ethos stuff’ that are dynamically interrelated. The significance of the new technical stuff largely has to do with how it enables people to build and participate in literacy practices that involve different kinds of values, sensibilities, norms and procedures, and so on, from those that characterize conventional literacies. These values, sensibilities, etc. comprise the ‘new ethos stuff’ of new literacies."

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2007). Researching new literacies: Web 2.0 practices and insider perspectives. E-learning, 4(3), 224-240.

"The kinds of technological trends and developments we think of as comprising new technical stuff represent a quantum shift beyond typographic means of text production as well as beyond analogue forms of sound and image production. New technical stuff can, of course, be employed to do in new ways ‘the same kinds of things we have previously known and done’ – and often is (Hodas, 1996; Bigum, 2003). Equally, however, this new technical stuff can be integrated into literacy practices (and other kinds of social practices) that in some significant sense represent new phenomena. The extent to which they are integrated into literacy practices that can be seen as being ‘new’ in a significant sense will reflect the extent to which these literacy practices involve different kinds of values, emphases, priorities, perspectives, orientations and sensibilities from those typifying conventional literacy practices that became established during the era of print and analogue forms of representation and, in some cases, even earlier."

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2007). Researching new literacies: Web 2.0 practices and insider perspectives. E-learning, 4(3), 224-240.

"For present purposes, much of what we regard as new ‘ethos stuff’ in contemporary practices is crystallized in current talk of ‘Web 1.0’ and ‘Web 2.0’ as different sets of design patterns and business models in software development, and in concrete examples of how the distinction plays out in real life cases and practices mediated by the Internet (O’Reilly, 2005).

The first generation of the Web has much in common with an ‘industrial’ approach to material productive activity. Companies and developers worked to produce artefacts for consumption. There was a strong divide between producer and consumer. Products were developed by finite experts whose reputed credibility and expertise underpinned the take-up of their products. Britannica Online stacked up the same authority and expertise – individuals reputed to be experts on their topic and recruited by the company on that basis – as the paper version of yore. Netscape browser development proceeded along similar lines to that of Microsoft, even though the browser constituted free software. Production drew on company infrastructure and labour, albeit highly dispersed rather than bound to a single physical site.

The picture is very different with Web 2.0. Part of the difference concerns the kind of products characteristic of Web 2.0. Unlike the ‘industrial’ artefactual nature of Web 1.0 products, Web 2.0 is defined by a ‘post-industrial’ world-view focused much more on ‘services’ and ‘enabling’ than on production and sale of material artefacts for private consumption. Production is based on ‘leverage’, ‘collective participation’, ‘collaboration’ and distributed expertise and intelligence, much more than on manufacture of finished commodities by designated individuals and work teams operating in official production zones and/or drawing on concentrated expertise and intelligence within a shared physical setting."

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2007). Researching new literacies: Web 2.0 practices and insider perspectives. E-learning, 4(3), 224-240.

"This means that being an ‘insider’ to a new literacy practice presupposes sharing the ethos values in question; identifying with them personally. Consequently, what may look on the surface like engagement in a new literacy may well turn out upon closer examination not to be. For example, simply downloading video clips from a popular participatory site like YouTube.com to accompany lectures, without otherwise engaging in any of the forms of participation that characterize engagement in a fan practice site does not, for us, rank as a new literacy practice. It is the cultural equivalent of cutting a picture out of a magazine to use as an illustration in a handwritten story or project. As we have noted elsewhere (Lankshear & Knobel, 2003, 2006), in contexts of using new technologies a lot of old wine comes in new bottles at the interfaces of literacy and new technologies."

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2007). Researching new literacies: Web 2.0 practices and insider perspectives. E-learning, 4(3), 224-240.

2006

2005

2004

"Many recent studies on literacy have addressed the question of the social construction of literacy. For example, it has been argued that "web literacy should be understood as literacies, and furthermore as socially situated practices rather than technologically determined conventions of reading and writing" (Karlsson 2002). Literacy as a social practice means that it is always bound to the societal and social contexts of different domains of life, and is historically situated and constantly evolving. (Barton and Hamilton 1998, Warschauer 1999, The New London Group 2000). Following this view, web literacy in the present study is understood as a set of social and cultural practices of reading and writing in relation to different media objects on the web."

Ahtikari, J., & Eronen, S. (2004). On a journey towards web literacy--The electronic learning space Netro. A dissertation submitted at the University of Jyvaskyla Department of Languages. Retrieved September, 26, 2005.

Ahtikari, J., & Eronen, S. (2004). On a journey towards web literacy--The electronic learning space Netro. A dissertation submitted at the University of Jyvaskyla Department of Languages. Retrieved September, 26, 2005.

"The web can be seen as one large community of users from all over the world. On a macro level, this community shares the basic conventions of using the web, such as conventions of navigation, storing information and interaction. In addition, there are many sub-communities on the web, such as communities of professionals, which can be either local or global. A web user, thus, is a part of many communities, the members of which often have shared social conventions and literacy norms. By participating in the discourses of different communities, also new, perhaps less proficient members of the communities have a chance to acquire these shared conventions. Reading and writing on the web is thus a process in which the web user uses his or her prior knowledge to integrate the new information into his or her prior knowledge according to shared conventions. If we understand web literacy as a social practice it also follows that it is historically situated and constantly changing. Changes in literacy reflect the changes in various areas of society: in personal lives, in communities, in education and in working lives. (The New London Group 2000:10-19). At least in many western societies, the web is an influential medium causing changes in literacy practices of working, public and private lives. The web functions as a new source of information demanding new strategies of handling this information, as well as brings along new ways of communicating. Reading and writing related to work and personal lives is ever more often connected to using the web, and web literacy practices have become an integral part of society functions (see eg. Warschauer 1999:4)."

Ahtikari, J., & Eronen, S. (2004). On a journey towards web literacy--The electronic learning space Netro. A dissertation submitted at the University of Jyvaskyla Department of Languages. Retrieved September, 26, 2005.

Ahtikari, J., & Eronen, S. (2004). On a journey towards web literacy--The electronic learning space Netro. A dissertation submitted at the University of Jyvaskyla Department of Languages. Retrieved September, 26, 2005.

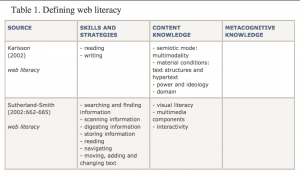

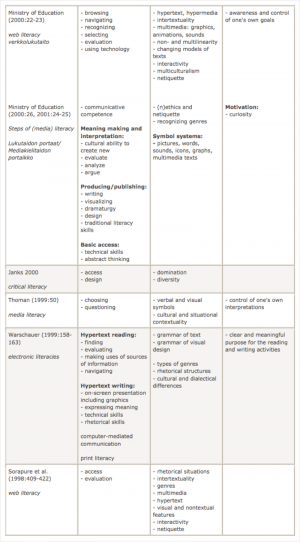

"Through exploring the different definitions and analysing them more carefully we created a framework of three interrelated fields of web literacy, in which the definitions themselves were divided into three categories of web literacy. Accordingly, we argue that web literacy is involved with areas of skills and strategies for using the web (ch 2.3.1), content knowledge of the multimodal medium (ch 2.3.2), as well as metacognitive knowledge of oneself as a web user (ch 2.3.3) (see Figure 3). We want to emphasise that this division should be regarded as a tool for understanding the many- sidedness and depth of the concept of web literacy, and not to be treated as a strict categorisation. Although the concept is perceived through these three separate fields, it is important to notice that none of them exists independently and they cannot be separated from each other. On the contrary, all of the aspects discussed are interdependent, and together form what we understand that web literacy is."

Ahtikari, J., & Eronen, S. (2004). On a journey towards web literacy--The electronic learning space Netro. A dissertation submitted at the University of Jyvaskyla Department of Languages. Retrieved September, 26, 2005.

"Despite the variety of perspectives and contexts in which web literacy has been approached, a general tendency seems to be that the research on web and media literacy often emphasise the skills and strategies connected to the content and form of the web. This is illustrated in the Table 1, for the content of the first column of skills and strategies seems to override the other two areas of web literacy. Warschauer (1999:1), too, points out that literacy is often viewed as "skills that can be imparted to individuals". Attempts to teach web literacy, accordingly, often concentrate on providing students with detailed guidelines of what to do and how on the web. However, there are a number of reasons for a need for a shift in perspective. Firstly, the web being a dynamic, continuously developing environment, at least teaching technical skills does not in the long run support the development towards autonomous managing of the web. Secondly, the sets of skills require content knowledge, that is, knowledge on what this multimodal medium is like, how it functions and how texts in this medium are constructed. Thirdly, as we view web literacy through socio-constructive lenses, and understand reading and writing on the web as meaning making processes closely connected to the social and historical contexts, there is a need to raise awareness on how you function as a reader and a writer, and how meanings are constructed. Finally, it is quite understandable that when raising awareness, there is a need to go beyond what you already are aware of, know, and can do. Thus, we want to shift the focus in this study from skills and strategies related to web towards the other two fields of web literacy, the content knowledge and metacognitive knowledge of the web."

Ahtikari, J., & Eronen, S. (2004). On a journey towards web literacy--The electronic learning space Netro. A dissertation submitted at the University of Jyvaskyla Department of Languages. Retrieved September, 26, 2005.

"Our goal when defining web literacy has been to build a working definition that can be used for the pedagogical purpose of supporting the learner to develop towards web literacy as autonomous managing on the web. Because of this, we find it important to change the focus from the skills to both content knowledge and especially to metacognitive knowledge. For we argue that it is only through building your metacogniton that you can strive for independence when faced with a medium such as the web. Without an awareness of yourself as a web reader and writer, the nature of web literacy is less self- directive, and adapting to the changes in the medium and its content is more difficult."

Ahtikari, J., & Eronen, S. (2004). On a journey towards web literacy--The electronic learning space Netro. A dissertation submitted at the University of Jyvaskyla Department of Languages. Retrieved September, 26, 2005.

2003

2002

2001

2000

"One objective of the International Multiliteracies Project... is to develop an educationally accessible functional grammar; that is, a metalanguage that describes meaning in various realms. These include the textual and the visual, as well as the multimodal relations between the different meaning-making processes that are now so critical in media texts and the texts of electronic multimedia.

Any metalanguage to be used in a school curriculum has to match up to some taxing criteria. It must be capable of supporting sophisticated critical analysis of language and other semiotic systems, yet at the same time not make unrealistic demands on teacher and learner knowledge, and not immediately conjure up teachers' accumulated and often justified antipathies towards formalism. The last point is crucial, because teachers must be motivated to work on and work with the metalanguage.

A metalanguage also needs to be quite flexible and open ended. It should be seen as a tool kit for working on semiotic activities, not a formalism to be applied to them. We should be comfortable with fuzzy-edged, overlapping concepts. Teachers and learners should be able to pick and choose from the tools offered. They should also feel free to fashion their own tools. Flexibility is critical because the relationship between descriptive and analytical categories and actual events is, by its nature, shifting, provisional, unsure, and relative to the contexts and purposes of analysis.

Furthermore, the primary purpose of the metalanguage should be to identify and explain differences between texts, and relate these to the contexts of culture and situation in which they seem to work. The metalanguage is not to impose rules, to set standards of correctness, or to privilege certain discourses in order to "empower" students."

Cazden, C., Cope, B., Fairclough, N., Gee, J., Kalantzis, M., Kress, G., ... & Nakata, M. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard educational review, 66(1), 60-92.

Cognitive flexibility theory (Jacobson & Spiro, 1995; Spiro & Jehng, 1990), for instance, suggests that learning about a complex, ill-structured domain requires numerous carefully designed traversals (i.e., paths) across the terrain that defines that domain, and that different traversals yield different insights and understandings. Flexibility is thought to arise from the appreciation learners acquire for variability within the domain and their capacity to use this understanding to reconceptualize knowledge."

McEneaney, J. E. (2000). Learning on the Web: A Content Literacy Perspective.

One significant problem with the web is that it is still so new that conventions have yet to emerge. This means readers need to devote energy and attention to processes that are usually automatic in traditional print. How do I find the index page in a complex document I've dropped into from a search engine? How do I know if a link takes me to a different section of the same document or to completely different material? How much confidence can I have that the material I am reading is factually accurate or authoritative in some way? How do I get back to where I started? As users of traditional print, we face the same kinds of problems, but we have ready responses. Tables of contents are at the front. Distinct documents usually appear in separate chapters or books, articles or journals. We generally know something about the reputations associated with publishers of printed materials, and we have learned to rely on dog-ears, pencil marks in margins, and page numbers to help us track our progress. But we don't yet quite know all the ins and outs of "webliteracy," and compounding the problem is the fact that the new technologies preserve much of the capabilities of the old ways while introducing new elements. The result is increased opportunities for complexity and as we increase complexity, we increase demands on those who seek to use the materials we produce."

McEneaney, J. E. (2000). Learning on the Web: A Content Literacy Perspective.

"As Richard Ohmann has shown, contemporary usage of the word literacy has its roots in the anxieties of nineteenth-century middle-class cultural about the working classes, especially immigrants. As a social category, the notion of an exclusively "literate public" performed cultural work for diverse political persuasions: it was a means of exclusion by which cultural conservatives could distinguish themselves as fundamentally different from the "illiterate" masses, while liberals used it as a strategy of social containment whereby they could "help" the lower orders and thus exert paternalistic control over them."

Stroupe, C. (2000). Visualizing English: Recognizing the hybrid literacy of visual and verbal authorship on the web. College English, 607-632.

""[E]ach medium arises by building recursively upon its predecessor," writes John McDaid, "taking the previous technology as 'content'" (209). More suggestively, as Gary Heba argues, new communication technologies appropriate not just the content of the older ones, but "the literacies required to read and interpret the earlier technologies in a process of 'repurposing' information, that is, using certain features of older communication technologies in the newer ones" (20)."

Stroupe, C. (2000). Visualizing English: Recognizing the hybrid literacy of visual and verbal authorship on the web. College English, 607-632.

1999

"The challenge for literacy researchers is to extend and enhance understanding of the ways in which the use of new technologies influences, shapes, perhaps transforms, literacy practices. Whether the changes to the literacy landscape we are witnessing represent an extension of the ways in which we do literacy or something altogether different, changes are happening. We need to investigate the nature of these changes to literacy practices and find illuminating ways to theorise them that are useful for teachers."

Snyder, I. (2000). Literacy and technology studies: Past, present, future. The Australian Educational Researcher, 27(2), 97-119.

"Integral to a sociocultural approach to literacy is the understanding that literacy is more than the capacity to encode and decode - to grasp meanings inscribed on a page or a screen, or within an established social practice (Street 1984). Being literate also involves the capacity and disposition to scrutinise the practices and universes of meanings within which texts are embedded. Being literate entails the capability to enter actively into creating, shaping and transforming social practices and universes of meanings in search of the best and most humane of all possible worlds."

Snyder, I. (2000). Literacy and technology studies: Past, present, future. The Australian Educational Researcher, 27(2), 97-119.

1998

The Bruce and Hogan article is remarkably prescient.

"We tend to think of technology as a set of tools to perform a specific function. These tools are often portrayed as mechanistic, exterior, autonomous, and concrete devices that accomplish tasks and create products. We do not generally think of them as intimately entwined with social and biological lives. But literacy technologies, such as pen and paper, index cards, computer databases, word processors, networks, e-mail, and hypertext, are also ideological tools; they are designed, accessed, interpreted, and used to further purposes that embody social values. More than mechanistic, they are organic, because they merge with our social, physical, and psychological beings. Thus, we need to look more closely at how technologies are realized in given settings. We may find that technological tools can be so embedded in the living process that their status as technologies disappears."

Bruce, B. C., & Hogan, M. P. (1998). The disappearance of technology: Toward an ecological model of literacy. p2.

"Thus, writing is no longer viewed as a technology; instead, only its newest manifestations take on that role. Each literacy technique-quills, movable type, ballpoint pens, typewriters-passes through phases of technology to tool, from unfamiliar to familiar, and from visible to invisible. Already, word processing, once a new technology, is now considered to be just the way people write. Web page writing conceived as a new technology ability today, will not be so in a few years.

Further, as a tool becomes embedded in social practices, our conception of the ability required for an individual to use that tool changes as well. In the early stages of use, disability is counted as a flaw in the tool: We say that poor design of the technology makes it difficult to use. Later, the disability becomes an attribute of the user, not the tool. We say that the user needs more training, or worse, is incapable of using the tool. Once the status of the tool as technology has fully merged into daily practice, the disability to use it becomes an essential attribute of certain people.

[...]

This process is one of the crucial ways in which all literacy technologies-slate tablets, typewriters, word processors, networks, computer interfaces, databases, the Web-are ideologically embedded. Effective use of the dominant reading and writing technologies then becomes the defining characteristic for new forms of literacy (Bruce, 1995). Lack of such ability can be conceived as an inherent disability, located in the individual, which might or might not be alleviated through various measures, such as providing more time, easier texts, skill training, tutoring, help features, donations of equipment, and so forth."

Bruce, B. C., & Hogan, M. P. (1998). The disappearance of technology: Toward an ecological model of literacy. p3.

"Embedded systems may entail a loss of control in one sense. Fewer people will be able to fix their own cars or any number of household appliances. They will need to rely more on experts, and they will need to pay for that expertise. On the other hand, these systems can create a more user-friendly world, what some have called "soft technology" (Norman, 1993). Their overall effect will depend on the social conditions and power relations that surround their use.

Similarly, literacy tools are becoming embedded systems. For an increasing number of people, writing means typing on a personal computer, reading means browsing a newspaper on the Internet, and researching means accessing a library database via modem. If a computer hard drive crashes while using today's literacy tools, most people will need to rely on an expert to fix it. Literacy today is becoming dependent on embedded systems that are invisible to the user.

One implication of this embedded technology is that we need to look more carefully at how technology is affecting our lives even when we cannot see it directly. Literacy means not just reading and writing texts, but "reading" the world, and the technological artifacts within it."

Bruce, B. C., & Hogan, M. P. (1998). The disappearance of technology: Toward an ecological model of literacy. p4-5.

"People write social relations through the languages of technology, constructing hierarchies and fields of inclusion or exclusion through silicon chips, wires, and video displays. The sentences we write with technologies describe our social life, as surely as the cave paintings of Lascaux or the Mayan calendar tell tales of earlier social worlds. However, technologies also serve to prescribe, to turn social intentions into tangible realities. Latour (1991) encapsulates this point as, "technology is society made durable" (p. 103)."

Bruce, B. C., & Hogan, M. P. (1998). The disappearance of technology: Toward an ecological model of literacy. p6.

"According to Rifkin (1995), the two problems indicate a growing dual, or cleaving, economy for the 21st century. The cleaving, Rifkin warns, will occur both nationally and globally. The first economy, the utopian one, will be made up of highly trained, well-educated knowledge workers in an information-based economy. The second economy, for the reserve of other workers, will be struggling with unemployment, part-time work, and jobs left in the service sector, such as waitressing, construction, automotive maintenance, painting, and so forth. Thus we find two economies and a growing chasm between them. As Rifkin (1995) suggests, "Ironically, the closer we seem to come to the technological fruition of the utopian dream, the more dystopian the future seems" (p. 56). Literacy no longer means just reading and writing to secure a decent job, even one that does not require much of either. Literacy means reading the technological world, including the relation of technologies to these dual economies."

Bruce, B. C., & Hogan, M. P. (1998). The disappearance of technology: Toward an ecological model of literacy. p14.

1997

"Technologies participate intimately in the construction of all literacy practices. They are not separate from texts and meaning making, but rather are part of how we enact texts and make meaning. We make texts material through technologies of papyrus, paper, chalkboard, or electronic screen. We also con- tinually redefine what counts as text through these technologies: Novelists write hypertexts, advertisers write in multimedia, and encyclopedias move from paper to digital media."

Bruce, B. C. (1997). Literacy technologies: What stance should we take?.

Official Journal of The Literacy Research Association. p300.

"...the technologies of literacy are not optional add-ons, but are part of the definition of every form of literacy. Thus, a theory of literacy in a particular setting or community needs to incorporate an analysis of the relevant technologies, much as we more often include analyses of textual content, pedagogical procedures, personal backgrounds, or institutional agen- das. That we often do not incorporate such an analysis may be due in part to im- plicitly assuming that those technologies are known and fixed. But when we look at literacy cross-culturally, or historically, that assumption becomes untenable."

Bruce, B. C. (1997). Literacy technologies: What stance should we take?.

Official Journal of The Literacy Research Association. p304.

Bruce, B. C. (1997). Literacy technologies: What stance should we take?.

Official Journal of The Literacy Research Association. p305.

"The literacy practices one can engage in are to a large extent a function of the available technologies and not a property of the individual. The power of digital technologies to make possible new forms of literate practices thus leads us naturally to a transformative stance on technology.

Instead of just asking, will there be equity or inequity as a result of new technologies, we might start instead with, “What sort of society do we want?” With this frame, we see that if rich schools get all the new computers, it is not that things just happened to work out that way, but rather that we as a society chose to selectively empower one group at the expense of another through tech- nology. New technologies make it easier to carry out society’s agenda; the key is- sue is what that agenda should be."

Bruce, B. C. (1997). Literacy technologies: What stance should we take?.

Official Journal of The Literacy Research Association. p306.

1996

"Information and computer literacy, in the conventional sense, are functionally valuable technical skills. But information literacy should in fact be conceived more broadly as a new liberal art that extends from knowing how to use computers and access information to critical reflection on the nature of information itself, its technical infrastructure, and its social, cultural and even philosophical context and impact - as essential to the mental framework of the educated information-age citizen as the trivium of basic liberal arts (grammar, logic and rhetoric) was to the educated person in medieval society."

Shapiro, J. J., & Hughes, S. K. (1996). Information Literacy as a Liberal Art: Enlightenment proposals for a new curriculum. Educom review, 31(2). p3.

Recommendations from Shapiro & Hughes (1996) as to what an 'information literacy as a liberal art' curriculum should include:

- Tool literacy - "the ability to understand and use the practical and conceptual tools of current information technology, including software, hardware and multimedia, that are relevant to education and the areas of work and professional life that the individual expects to inhabit"

- Resource literacy - "the ability to understand the form, format, location and access methods of information resources, especially daily expanding networked information resources."

- Social-structural literacy - "knowing that and how information is socially situated and produced."

- Research literacy - "the ability to understand and use the IT-based tools relevant to the work of today's researcher and scholar."

- Publishing literacy - "the ability to format and publish research and ideas electronically, in textual and multimedia forms.".

- Emerging technology literacy - "the ability to ongoingly adapt to, understand, evaluate and make use of the continually emerging innovations in information technology so as not to be a prisoner of prior tools and resources, and to make intelligent decisions about the adoption of new ones."

- Critical literacy - "the ability to evaluate critically the intellectual, human and social strengths and weaknesses, potentials and limits, benefits and costs of information technologies."